|

With 63 mathematical stories under his name and a total sale volume of 14+ million copies sold worldwide, Stuart J. Murphy (Illinois / Massachusetts) is the world's most prolific and best-selling mathematical story author. Stuart has single-handedly authored these 63 mathematical stories as part of his MathStart series (published by HarperCollins). To learn more about his stories, simply click on the book covers below. If you wish to purchase a full set of MathStart books, you can find out more details here. (For 'full-set' sales outside the US, e-mail [email protected] for more information). We hope you enjoy reading Stuart sharing his experience of working on this wonderful mathematical story series with you! If you can't get enough of Stuart, TeachingBooks.net features three-part four-minute mini-documentary videos of Stuart talking about his MathStart series here. Connect with Stuart: |

|

Happy 75th Birthday – four days in advance – Stuart! How do you plan to celebrate your birthday?

I have very special plans for my birthday this year. We will be in Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic, getting ready to board a river boat for a cruise down the Danube River the following morning. That night, we have a large dinner party planned with the group of 22 friends who will be traveling with us. This trip has nothing to do with my birthday but I know the event will be celebrated in style! What are three interesting or weird facts about you? :-)

What inspired you to write books about maths? I worked in educational publishing my entire career. This gave me the opportunity to work with top educators in all disciplines, including mathematics. I also had the chance to visit classrooms and present my ideas to teachers and students. During one experience, I was presenting to a group of students who were regarded as “reluctant learners.” They just weren’t interested. After working with them for a few days, I found that they became interested when the maths were presented within a context of something they cared about, in this case, current music trends. Before long, they were creating charts and graphs that described the rise of certain popular musicians, presenting arguments based on their findings regarding the popularity of different types of music, and even making predictions about future developments in the field. They became excited about the power of maths. I thought, well, if this works for older students maybe it can help younger kids become more interested in mathematics. That led to the creation of my first three books, ‘The Best Bug Parade’, ‘Give Me Half!’, and ‘Ready, Set, Hop!’. Why did you start with these three books? And did you ever imagine that the series would grow into 63 books, that it would get translated into several languages, receive many prestigious awards, with 12 million copies sold worldwide, and even a musical based on some of the stories in the series? I began with these three books because I wanted to experiment with books that were appropriate to three different age levels, 3-5, 5-7, and 7-9. The overlap was intentional as all kids aren't the same at any given age. As only my wife, Nancy, knew, I was already envisioning a series of 12 books. I’m not sure who I thought I was. I didn’t even have one book published at the time. Well, after my original contract for three was completed, it wasn’t long before I did have a contract for 12, and then 24, and finally a total of 63 books. The three age groupings became known as Levels 1, 2 and 3. I feel very fortunate to have had this opportunity. "When I was working on book number 45 or 46, my editor called having just left a meeting where the publisher was deciding on how far to extend my contract. She asked, "How many maths concepts are there?” My response was, “We’re just at the beginning.”"

You have covered a wide variety of mathematical topics. How do you settle on these specific topics and are there any you haven’t covered in the series? I spent a lot of time with teachers talking about what maths concepts were most difficult for their students to easily grasp. I also studied the standards that are produced by states that define what should be taught at each grade level, and more recently the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. I tried to select topics that are especially complex for children, that bridge areas of learning, or that use multiple mathematical ideas. For example, students have a lot of trouble making the transition from adding to building equations ('Animals on Board'). Learning about doubling (‘Double the Ducks’) leads to counting by 2’s, 3’s and 4’s (‘Spunky Monkeys on Parade’), and then expands to multiplication (‘Too Many Kangaroo things to Do!’). Estimating uses multiplication, addition and rounding (‘Betcha!’). When I was working on book number 45 or 46, my editor called having just left a meeting where the publisher was deciding on how far to extend my contract. She asked, "How many maths concepts are there?” My response was, “We’re just at the beginning.” There are topics like the relationship of fractions to decimals, and the reinforcement of number sense, that I would still like to tackle. What about the contexts — the storylines? How do you select those? My storylines have always been inspired by what kids actually say and do. My own children have inspired many of my stories. ‘Give Me Half!’ is a good example. We have a boy and a girl who are about four years apart and sharing equally was always a problem when they were growing up. My three grandchildren have provided inspiration as I have watched them interact with friends and participate in activities both in and outside of school. I have been known to ask kids to empty their backpacks and show me what’s inside. Watch out. That can be scary! I have also followed kids in stores to see what interests them as they look at books and magazines or clothing. Some friends have joked that I might be arrested someday for following kids around. I always keep folders of things that look appealing and that have maths consequences to them. I find it valuable to clip things out of newspapers about the Olympics, election results, or baseball scores, or to keep flyers from places I visit. I was once in Texas the week before the rodeo opened. It was such an exciting build-up with parades and wagon trains, and the establishment of tent and trailer living areas around the stadium. I had a chance to interview some of the performers over breakfast one morning. Notes were filed away in a folder. It wasn’t long before my book ‘Rodeo Time’ appeared in the series! This “on-the-ground” research has helped me greatly. This is why I write about bugs and bunnies, pets and families, friends and neighbors, and carnivals and sports events. Those are things that interest kids and are part of their lives. You worked with several illustrators as part of the MathStart series. How involved were you in the illustration process? Did you have a say in how mathematical models and diagrams ought to look like?

For many years, I worked as an art director. Also, my manuscripts are all visual/verbal in nature as much of the content of my books is in the illustrations. Therefore, I had the opportunity to participate in the selection of the illustrators and to work very closely with the editors and designers throughout the development of the sketches and finished art. The illustrators that were selected were fantastic and added greatly to the quality and creativity of the finished products. |

"I always say that there are three things in all my MathStart stories: words, pictures and math. Words are how we communicate with others using language. Pictures are also a part of our communication system. And, math, too, is a way to provide information to others." From our understanding, your background was not in math or writing per se, but in art. How did you transition into being a maths story author? I am often asked which came first, maths or writing, and I respond, “Neither. Art.” After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design, where I majored in Illustration, I was hired by Ginn and Company, an educational publisher, to work in the art and design department. In that position, I became very interested and more knowledgeable in how children learn from the visual images they see. That led to an increased commitment to the field of Visual Learning, which has become the focus on my career. I am still very active in educational publishing and am currently on the authorship teams of a number of mathematics programs published by Pearson Education. I also remained interested in the effectiveness of storytelling as a vehicle for teaching mathematical concepts. Why not put the three together? I always say that there are three things in all my MathStart stories: words, pictures and math. Words are how we communicate with others using language. Pictures are also a part of our communication system. And, math, too, is a way to provide information to others. You have been described as a Visual Learning Specialist. Can you say a few words about visual learning and visual literacy? When I first starting working in the field of visual learning, I called it “visual literacy.” I immediately had push-back from reading and language arts educators who felt that this was not a true ‘literacy’. At the time, the research wasn't there to validate it. I decided that I would switch to ‘visual learning’ as a descriptor of what I was doing. As I said at the time, “I don’t care what we call it. I just want us to do it.” Now that there is a body of research behind these strategies, I note that ‘visual literacy’ has crept back in as a phrase that is sometimes used to describe the field. I’m sticking with visual learning. "My goal has been to make sure that the series represents the world that kids see and that each child can readily identify with one or more of the characters in the stories."

Having written so many books, what are your thoughts on diversity in picture books? With 63 books in the series, I have had the opportunity to really think about diversity and how children are represented in stories. I have made sure that there are female and male protagonists, that there is racial diversity, and that there are different types of kids — tall and short, shy and bold, quiet and boisterous — in my stories. My goal has been to make sure that the series represents the world that kids see and that each child can readily identify with one or more of the characters in the stories. In a question and answer period during a school visit a number of years ago, a boy asked if I had something against cats because he thought I had more dogs than cats in my stories. Being a “dog person” — we have almost always had a dog in our house — I thought that he might be right. However, when I got home I carefully checked and found that, at that point, there were actually two more cats than dogs in the series. As the series progressed, I was very careful with the dog/cat count! What do you think are some of the key benefits of using the math and literature integration as a mathematics teaching and learning tool? I think that the use of literature and math together in the teaching of mathematics has greatly evolved over the past two or three decades. I would like to think that I, along with the other authors who write books that incorporate maths ideas, have had something to do with that. My presentations at NCTM (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics) and other professional meeting on this topic are almost always filled with enthusiastic teachers. More and more teachers now see the advantages of presenting mathematical concepts within the context of stories. It’s how we experience math in life — in the stories of our lives. It is also important to decontextualize maths concepts to show how the maths work. I try and do that through providing visual models that show what’s actually going on mathematically. That combination of contextualizing and decontextualizing provides students with a variety of entry points and multiple learning opportunities. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own maths picturebooks? Encouraging students to create their own maths picture books is an extremely valuable exercise. It encourages kids to consider the application of the mathematical concepts they have learned. Instead of asking, "When am I ever going to use this?", it gives them the opportunity to figure out where and how a maths concept can be applied. It helps them link maths to real life. It also broadens their conceptual understanding regarding what the concept is all about. An added benefit is that it truly engages the students in their maths learning. We often lament the fact that our kids aren't as interested in and positive about maths as we would like them to be. Producing their own books is a way to motivate them and get them excited about maths. Just think of how happy they will be to show their finished products to their friends, parents and grandparents. They will be proud of their maths! For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own maths picturebooks at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the process, what would be your advice? I would advise teachers (and parents) to:

In addition to MathStart, you have another series of books, 'I See I Learn' (published by Charlesbridge), that is not about maths. Instead, it presents social, emotional, health and safety, and cognitive skills in the contexts of stories. Can you tell us how this came about? Because MathStart includes the largest number of books that are designed for Pre-K and K, the 21 Level 1 books, I was often asked to present at early childhood conferences. I became very aware of the need for more resources that deal with social, emotional and related skills for young children. Research shows that self-regulation is one of the most reliable predictors of school success. Children who can’t cooperate with others, work in groups, make choices or control their own behaviors are not likely to easily learn mathematical skills. Children this age are often not reading yet but they are all seasoned visual learners. The combination of my interest in helping children be successful and my background in visual learning made this a natural pursuit. What do you think of the research that MathsThroughStories.org has conducted so far? MathsThroughStories.org documents the representation of girls and women in math-related picture books; shows relationships between creative writing skills and mathematical development, and traces the importance of the visualization of mathematical concepts as a key component of mathematics teaching and learning. These studies are extremely important and have a direct and positive impact on how mathematics is taught. I think these studies are crucial as they reinforce ideas that we have as educators of young children and validate the things that work in classrooms and homes. |

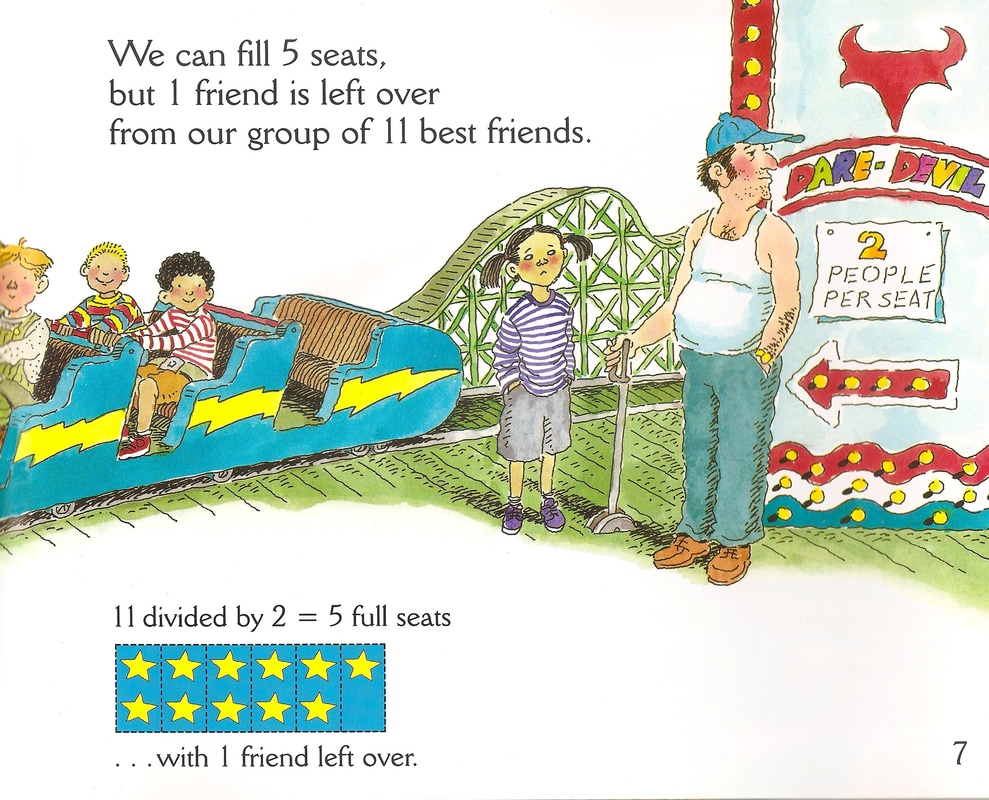

Illustrations copyright © 1997 by George Ulrich from Divide and Ride by Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins.

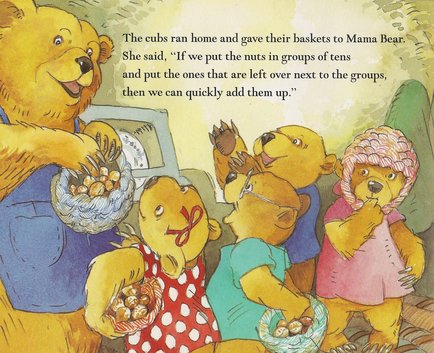

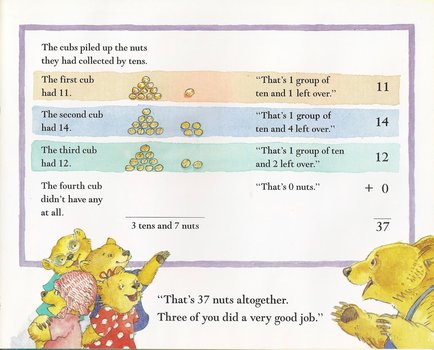

Illustrations copyright © 1998 by John Speirs from A Fair Bear Share by Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins.

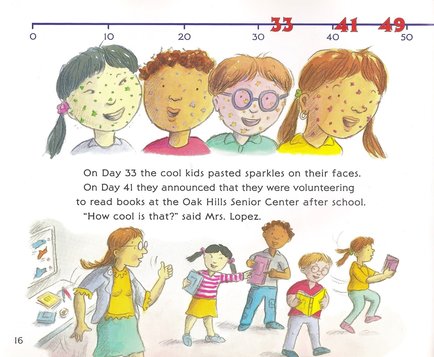

Illustrations copyright © 2004 by John Bendall-Brunello from 100 Days of Cool by Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins.

Illustrations copyright © 1998 by John Speirs from A Fair Bear Share by Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins.

Illustrations copyright © 2004 by John Bendall-Brunello from 100 Days of Cool by Stuart J. Murphy. HarperCollins.