|

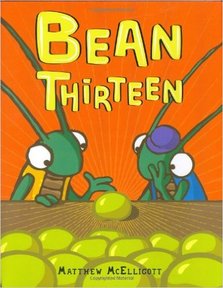

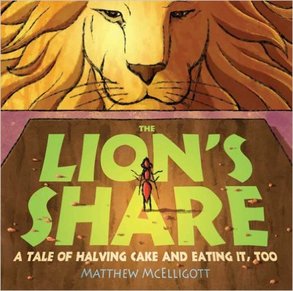

Matthew McElligott (New York) has authored and illustrated two of our favourite mathematical stories: 'Bean Thirteen' (2007), published by Putnam Publishing Group, explores properties of prime numbers, specifically 13, while 'The Lion's Share' (2009), published by Bloomsbury Publishing's Walker and Company, looks at the concepts of halving, doubling and fractions. To learn more about these stories, read our reviews, and find out where you can purchase them, simply click on their covers below. We hope you enjoy reading Matthew sharing his experience of working on these two mathematical book projects with you! |

|

First thing first, three interesting/weird facts about you :-)

What inspired you to write picturebooks with a mathematical focus?

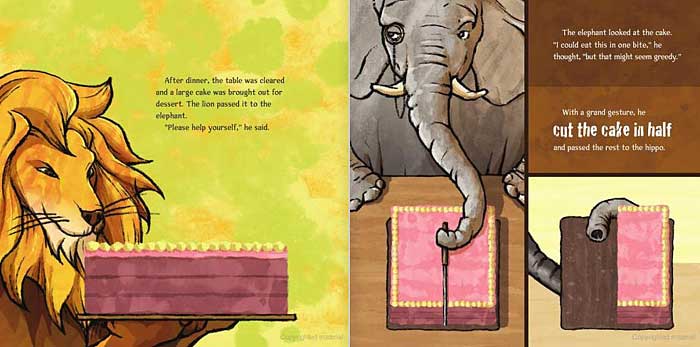

Growing up, math was not a strong subject for me. Too often it was taught without any context, and I struggled to understand it. Years later, as a grownup, I began to read some really good books about the history and the stories behind math (like Fermat’s Enigma by Simon Singh) and I began to see it in a whole new way. Now I’m a convert, and I want to share my excitement about math with the world. 'Bean Thirteen' and 'The Lion's Share' focus specifically on division and fraction respectively. What prompted you to focus on these topics? I didn’t set out to write about those topics specifically. 'Bean Thirteen' began when I read an article about why thirteen is considered unlucky. Since it’s a prime number, it’s terrible for dividing. But it’s next door neighbor, twelve, is a great number for dividing, since it has so many factors. This led to a story about prime numbers, superstition, and sharing. The idea for 'The Lion’s Share' came from one of my birthday parties. No one wanted to be greedy and take the last remaining piece of cake, so someone at the party decided to cut it in two, taking half the slice and leaving half for the next person. This continued around the table, and before long, the cake had been reduced to crumbs. I was fascinated by the math, the power of halving, that could produce such dramatic results.

How long did it take you to work on each of these books? From the first idea to writing the story to finishing the illustrations was a process of about two years for each book. What were some of the key stages that you went through in creating these picturebooks? The stories were developed first (see above), built around the mathematical concepts at their core. The illustration and design followed, but often ideas for the design would cause me to go back and rewrite parts of the story. Which of these stages did you find most difficult, and why? The hardest part for any book like this is to figure out a story that effectively explains and explores the subject in an entertaining way. The math has to be clear, but the story needs to be able to stand on its own. Most maths picturebooks have a team of author and illustrator working together. In your case, you authored and illustrated all by yourself. Did you find this a blessing or a curse, and why? Since the design of each book is directly related to the math concept in the story, it was really helpful to write and illustrate the books simultaneously. I could make changes to the pictures or the text as needed and allow the book to develop as a synthesis of the two. When you planned for page illustrations (particularly those that are mathematical in nature), what did you have to consider? The goal is always to have the story and the illustrations support one another. The design of 'The Lion’s Share', for example, directly reflects the halving and doubling of the story. The square shape of the book mirrors the shape of the cake, and as the cake is cut smaller and smaller, the sizes and positions of the illustrations change accordingly. Likewise, as the cakes double in the second half of the book, the framing of the illustrations doubles as well. (You can read more about this here) The characters in both of your books are animals. Why did you prefer having animal characters to human characters in these two stories? For 'Bean Thirteen', the characters needed to be small enough so that a single bean could be a plausible dinner, hence the use of insects. 'The Lion’s Share' is a book about doubling, and the size of the characters roughly doubles each time one is introduced. That way, each character’s size could relate mathematically to the size of the slice they cut, and the relative number of cakes they promise to bake. Closely related to the above point, some maths story authors prefer to have a context and setting as close to children’s real-world experience as much as possible. Others prefer fantasy. In the context of maths stories, what is your preference, and why? I think it really depends on the story. Any time you venture into the world of talking animals there has to be an element of fantasy, but the underlying themes of these books – superstition, greed, generosity, etc. – are universal and very real. These themes are where the reader makes the connection from their own lives to the experiences in the story. |

How do you know whether the language used in your stories is age-appropriate for your target children?

I don’t really think about this too much. I try to keep the story as clear as possible, and try to eliminate anything that doesn’t absolutely need to be there. With picture books, shorter is generally better, and learning to be spare and deliberate with the words in my stories has made be a better writer overall. On reflection of your maths picturebooks, how would you comment on the diversity of the books’ characters? Would you have done anything differently in terms of the diversity of the books’ characters? I’m happy to report that there are exactly the same number of female and male characters in each book. In terms of diversity, I’m proud to say that the books feature insect, reptile, amphibian, bird, and mammal characters. "The best way to learn a concept is to teach is or to make it. When children are challenged to apply their knowledge math to the construction of a story, they have to understand the material well enough to explain it to others."

What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to read maths picturebooks? We study math because it’s the language of the universe we live in. When we use math to tell stories, it gives those concepts context and application. A good math story teaches both the math and how the math relates to our own lives. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own maths picturebooks? The best way to learn a concept is to teach is or to make it. When children are challenged to apply their knowledge math to the construction of a story, they have to understand the material well enough to explain it to others. Do you think the use of storytelling in mathematics learning is only applicable to young children? Do you think this could be used in maths lessons in secondary schools too? Definitely. As I said before, I think a big reason why I was late to becoming a math fan was because of the lack of good math stories. Everyone loves a good story. I’m also a college professor, and regularly share my books with my students. There are many ways to read a story. A young child may read The Lion’s Share and see it as a story about animals sharing, while an older reader may pick up on the geometric sequences and binary arithmetic at its core.

For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own maths picturebooks at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the process, what would be your advice? Encourage kids to start by thinking about how they use math in everyday life. It can be something as simple as dividing up beans for dinner. Next, try to create a problem. For example, what if the number of beans is unlucky? What if that number can’t be shared evenly? These problems will create a story, as your characters work to find a solution. For teachers and parents who want to have a go at having their own maths picturebook published by a publisher, what would be your advice?

I have a page on my website with resources for aspiring writers. You can find it here. What do you think of the research that we do and the resources that we provide to teachers and parents on our MathsThroughStories.org website? I think these projects and resources are terrific, and will hopefully encourage more people to explore the use of storytelling to teach the fundamentals of mathematics. |

Illustrations copyright © 2007 by Matthew McElligott from Bean Thirteen by Matthew McElligott. Putnam Publishing Group.

Illustrations copyright © 2012 by Matthew McElligott from The Lion's Share by Matthew McElligott. Walker and Company.