|

Mary Murphy (Ireland) is the author of over 40 picture books and board books, including two of our favourite titles with an explicit mathematical focus: 'All the Little Ones and a Half' (2001) and 'Moonchap' (2003) - both of which are published by Flying Foxes, as well as a more recent title with an implicit mathematical focus for younger children: 'Mouse is Small' (2013) by Walker Books. To learn more about these stories, read our reviews, and find out where you can purchase them, simply click on their covers below. We hope you enjoy reading Mary sharing her experience of working on these incredible mathematical story projects with you! |

|

First thing first, can you tell us three interesting/weird facts about you :-)

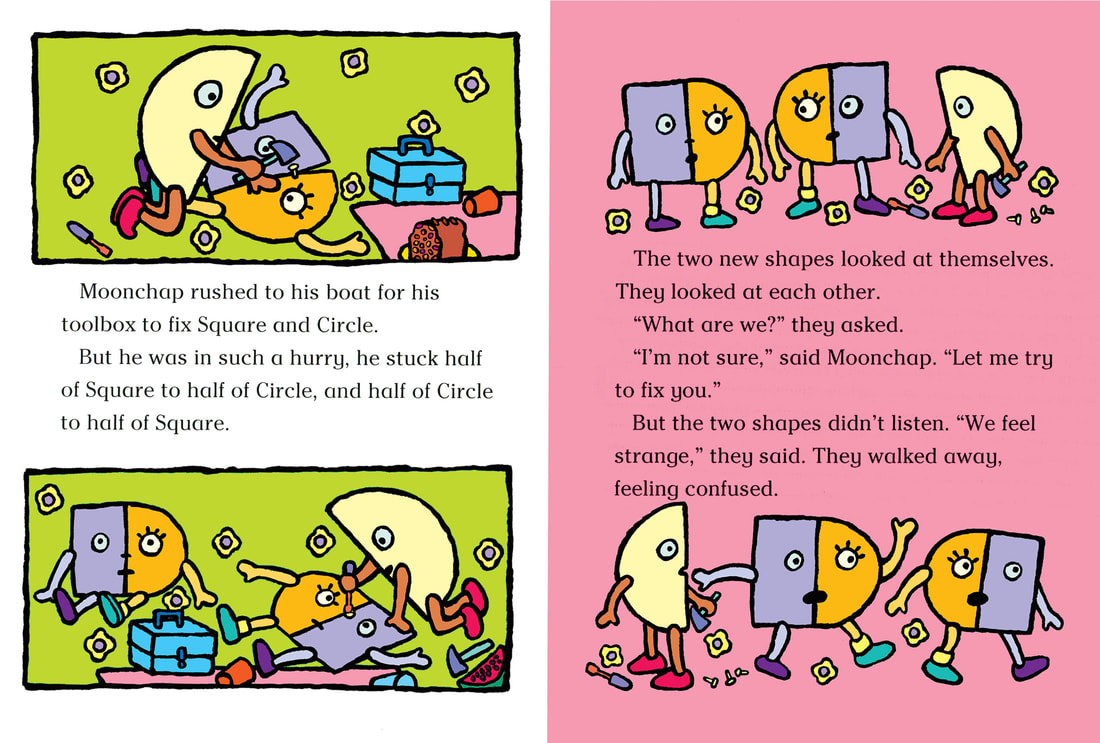

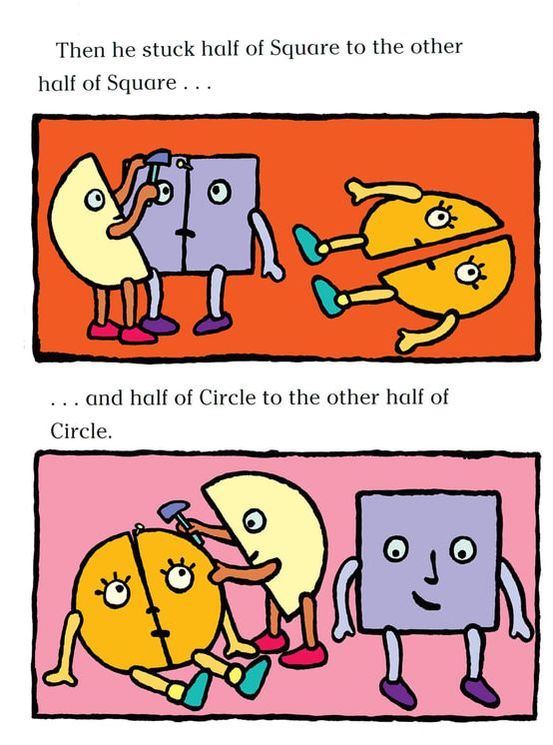

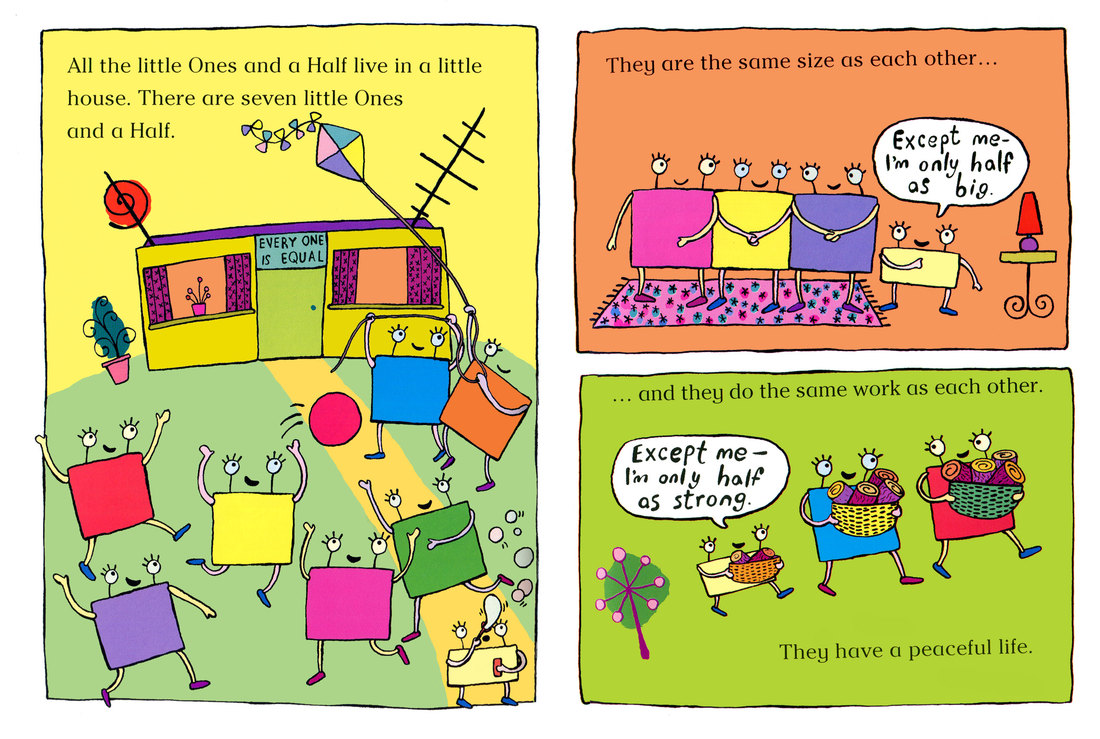

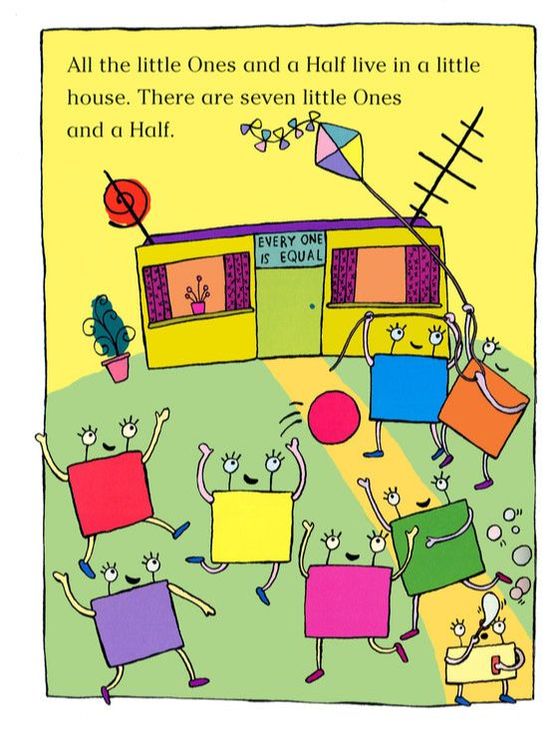

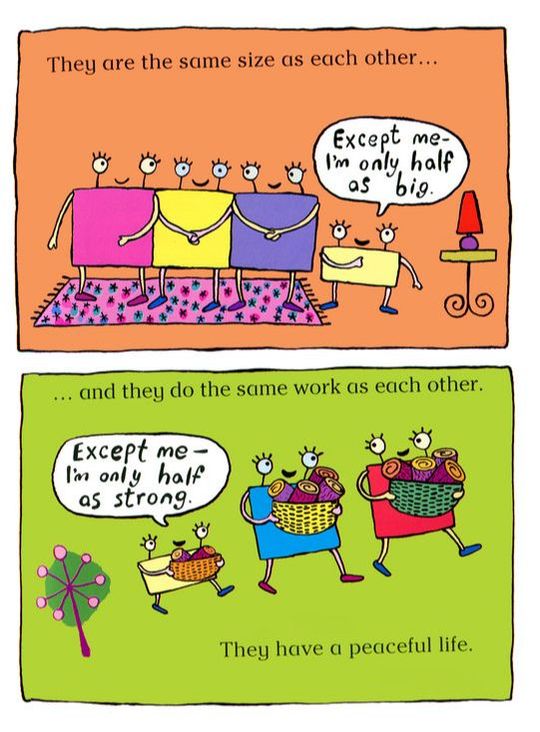

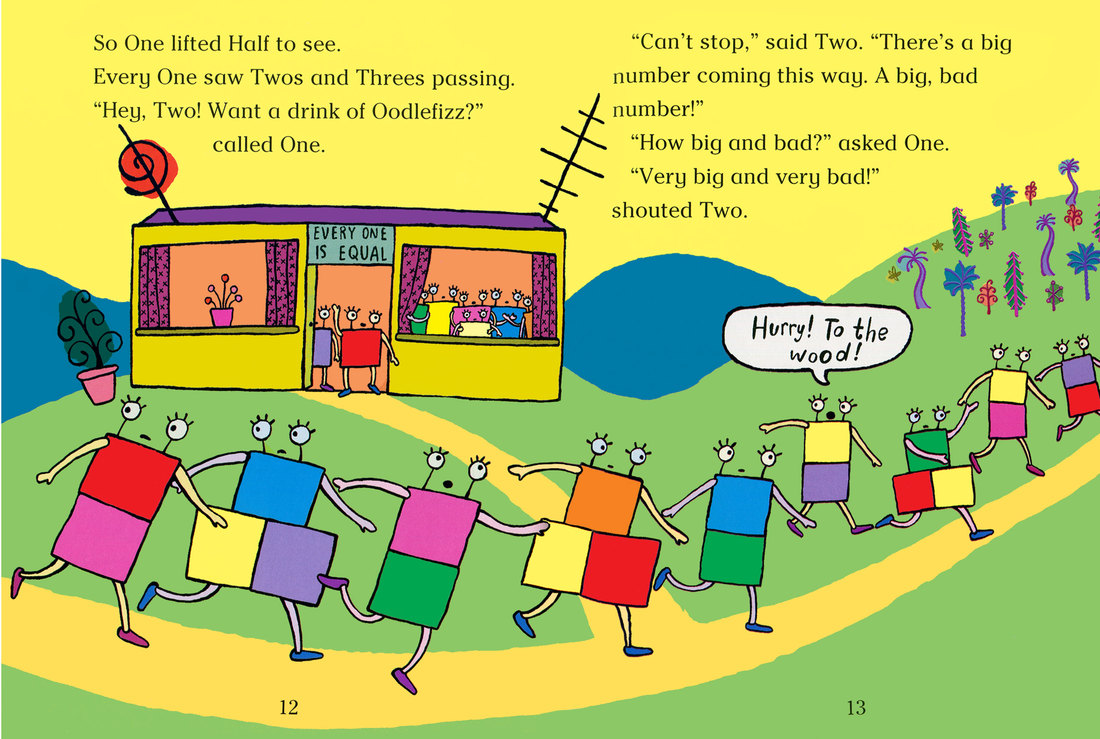

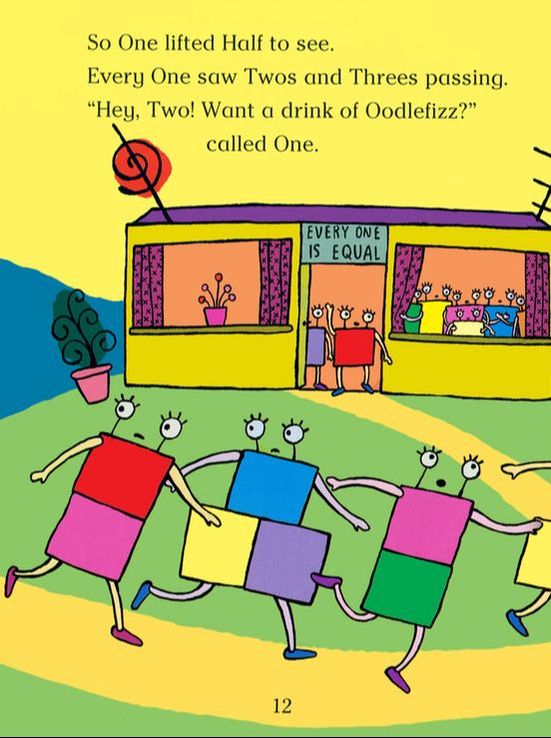

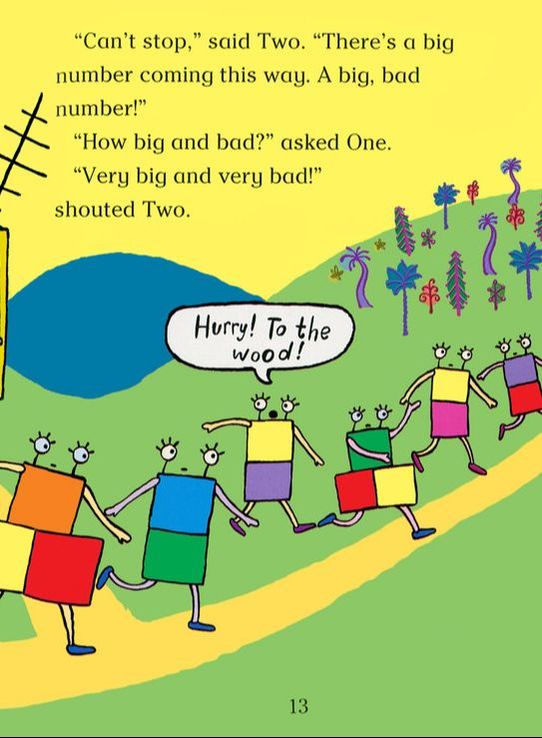

How would you describe your relationship with mathematics and mathematics learning when you were younger? And now? I enjoyed maths and was reasonably adept at it. I liked number and spatial puzzles, but I did sometimes find maths class a drag. Now I still like measuring, assessing spaces, figuring out numbers - though perhaps not doing the accounts. What inspired you to write picture books with a mathematical focus for young children? The publisher presented me, and other authors, with a list of possible curriculum-related themes, including mathematics, for a new booklist. I was taken with the idea of making stories about numbers as characters, so I had a go at it. Sometimes it is fun to see if you can respond to a brief creatively, rather than working solely from your own inspiration. Why do you prefer creating mathematical picture books with a storyline to, say, non-fiction mathematics concept books? I like all my books to have more than one layer, so for example in 'All the Little Ones and a Half' there are themes of bullying, friendship, sharing, ownership - as well as mathematics. That wouldn't really be possible in a non-fiction mathematics book. What are some of the key stages that you go through in creating your mathematical picture books? The curriculum elements of 'addition' and 'shapes' respectively were my starting points for 'All the Little Ones and a Half' and 'Moonchap'. I imagined small numbers and shapes as characters, and how they might interact. What problems or dramas might crop up between them, in keeping with them as mathematical entities? So the concept was given to me, the characters arose from that, and they generated their own stories. For 'All the Little Ones and a Half', the illustrations happened last; I had thought I would give the text to another illustrator. But as 'Moonchap' was the second book, I knew I would illustrate it, and wrote and illustrated in a more interconnected way. Which of these stages do you find most challenging? Similarly, which do you find most satisfying? One of the biggest challenges was figuring out how to make the numbers into visual characters, and it was very satisfying to achieve this. It was challenging (and satisfying) too to work out a story that adhered to both mathematical and dramatic principles. Do you find coming up with a storyline / context to embed your chosen mathematical concept in difficult? Where do you draw inspirations from? It felt quite natural to develop these mathematical stories. The inspiration really came from simply reflecting on the numbers and shapes as characters. Some mathematical story authors prefer to have a context and setting as closely related to children’s real-world experience as much as possible. Some prefer fantasy. In the specific context of mathematical stories, what is your preference, and why? I have only done two books in this genre, both of which are set in fantasy worlds. Again, the settings evolved from the characters - I couldn't have a Square, a Circle and a Crescent as characters in a 'real' world. However, the fantasy world still has to adhere to its own principles, it doesn't give you free rein. It's more fun working within constraints sometimes anyhow.

On average, how long did it take you to work on each of your mathematical picture books? Oops, can't remember... the writing didn't take very long, and as I remember the designer got married during the production of one of them which caused a happy delay. On average, from contract to publication, a picture book takes two years. But these two books were quicker as they could be published within the UK alone, without seeking co-publishers. (They are categorised I think as 'readers' rather than 'picture books'.) Most mathematical picture books have a team of author and illustrator working together. In your case, you authored and illustrated the stories all by yourself. Did you find this a blessing or a curse, and why? On 'All the Little Ones and a Half' I was a little taken-aback, on finding myself the illustrator, at the nasty task set for me by the author. But once I cracked how to form the characters, with stalk eyes and a floating mouth, so that a 3's body was exactly 3 times the size of a 1's body, and so on, it was fun. I write and illustrate almost all my books, so it is my norm. (And it means you earn both author and illustrator royalties.) How do you know whether the language used in your stories is age-appropriate for your target children? Do publishers normally have a word limit that you need to stick to? In the aforementioned booklist, there was a specific word count for each book, which my mathematical self enjoyed working to. Generally, your editor will pull you up if you use difficult words, or (I would say more commonly) complicated syntax. Books like this need to read aloud easily, so sentences should be quite short and clear. On reflection, how would you comment on the diversity of the characters in your mathematical stories? Would you have done anything differently in terms of the diversity of the characters? In 'All the Little Ones and a Half', the main character, Half, is a girl. She saves the day. This was a conscious decision. The 'baddie', Hundred, is male, which makes pronouns better pointers (i.e. having 'he' and 'she'). In the other book, 'Moonchap' is a handyman, and, since the book was dedicated to my brother (also a very handy chap), I made him male. Square (finnicky and houseproud) is male, Circle (slapdash and fun) is female. The characters are different colours and non-human, so ethnicities, social backgrounds etc. are not issues, I think. (Although the story for Moonchap ends as a migration story, welcoming people of 'all shapes and sizes'.) Can your fans expect to read any more stories with mathematical connections from you in the soon future? I would love to do more! But there is nothing like this in the pipeline right now. I did a book about sizes more recently for very little children, called 'Mouse is Small'. The pages get bigger as we meet bigger animals. (And the surprise end is that the smallest animal is the scariest) |

Do you have any favourite mathematical story author(s)? If so, which one, and which aspects of their works do you particularly like? There is a story in Jade Tales by Micheline Maurel and Annick Delhumeau, that I loved as a child. It is about a Minute who escapes from a clock at midnight, as I recall, and goes on a journey changing things by minute here, a minute there. I also liked counting books, which are visually so pleasing. Do you think teaching mathematics through storytelling could be used with secondary school students too? One program that can work well is to have older children read books to younger children. This is especially good for less-skilled readers, since the younger kids are so thrilled to be read to by a bigger person, they won't know or care if some words are incorrect, etc. "Interesting idea! 'Doing' always seems to have more impact than 'witnessing'. So it must be a powerful learning and affirming process to come up with your own story and make it into a book." What do you think are some of the key benefits of children developing their mathematical understanding through mathematical picture books? I imagine a child's understanding of the subject will deepen and embed more completely; we are so adept at integrating symbol through story. It's also likely, if it is an engaging story, that they will want to hear it or read it again, reinforcing their comprehension and confidence more each time. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own mathematical picture books? Interesting idea! 'Doing' always seems to have more impact than 'witnessing'. So it must be a powerful learning and affirming process to come up with your own story and make it into a book. I imagine acting it out, singing it, drawing it - anything like that would be helpful. For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own mathematical picture books at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the creative process, what would be your advice? It should be fun, first and foremost. Let the story follow their interests and imagination - football, dinosaurs, cooking, whatever. I think it might be easiest for the child to start with a character, and find a problem for them, and figure out how the problem is solved. Fantasy might not satisfy you, but it could easily satisfy the child. (Their fantasy world doesn't have to obey laws, giving them plenty of get-out-of-jail-free cards.) This probably won't result in a great story, but they'll enjoy it. Drawing or cutting out shapes can show the story, with few words. I think it is helpful with any age group to challenge their stereotypical thinking (especially around gender and ethnicity). It may be their prejudice, rather than their imagination, that creates a strong super-boy saving NumberTown from destruction. For teachers and parents who want to have a go at having their own mathematical picture book published by a publisher, what would be your advice? Inform yourself about your area. The Children's Writers' and Artists' Yearbook is a super resource if you're based in Ireland or the UK. If you're specifically developing a mathematical book, you're already doing something useful by browsing the Recommendations section of MathsThroughStories.org. If you've spotted a gap in the market, you could be on to something. If you're not an illustrator, don't illustrate your manuscript, and don't commission somebody else to do it - the publisher will have endless illustrators on hand. Make sure your idea can be rigorously interrogated by you and still stand up. Don't show it to other people unless asking for professional, informed advice. These books must read well aloud. Read it aloud - oh, forty times? - before you send it. This ensures the rhythms, sentence lengths, etc. work. Have a neutral other person read it aloud and listen for where they stumble, hesitate or misinterpret. Fix the tripping points. Make your idea as good as it can be before you send it out. With a mathematics story, you have to obey the rules of logic and mathematics - and this can give your character something to push against. "The research done by MathsThroughStories.org makes for fascinating reading, very convincing in terms of the positive role mathematical picture books have for children. The whole website is quite an Aladdin's cave, and is making me itch to create another mathematical book." What do you think of the research that we do and the resources that we provide to teachers and parents on our MathsThroughStories.org website? The research done by MathsThroughStories.org makes for fascinating reading, very convincing in terms of the positive role mathematical picture books have for children. The whole website is quite an Aladdin's cave, and is making me itch to create another mathematical book. |

Illustrations copyright © 2001 by Mary Murphy from All the Little Ones and a Half by Mary Murphy. Flying Foxes. All Rights Reserved.

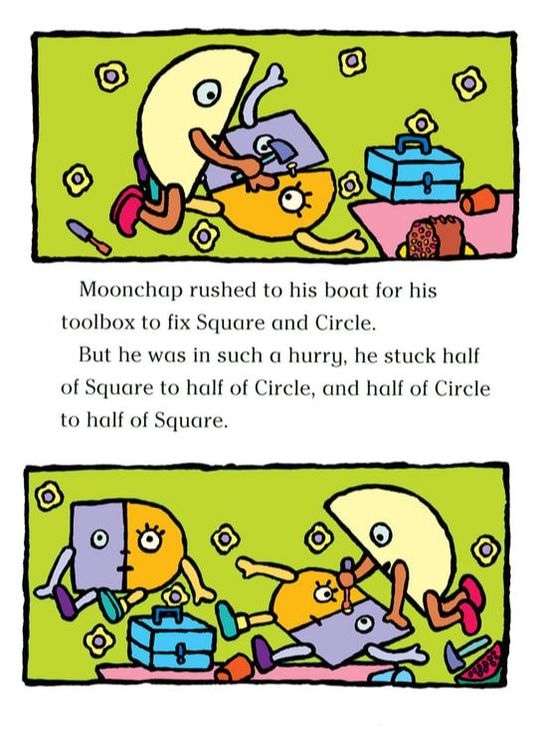

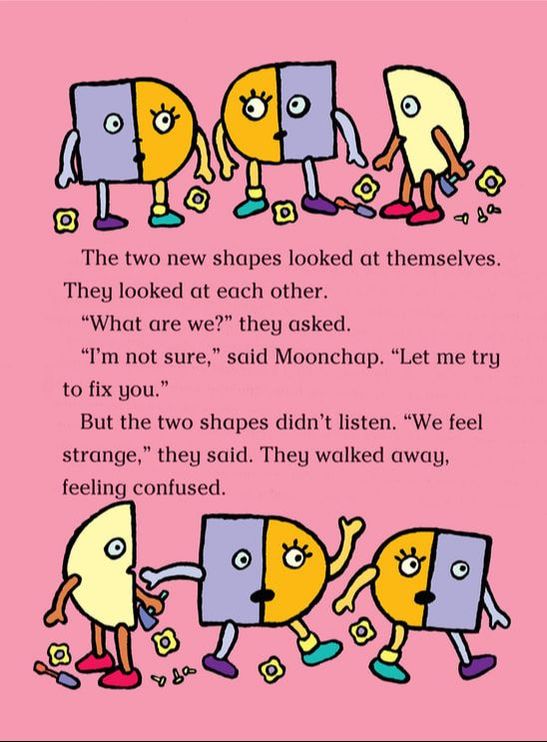

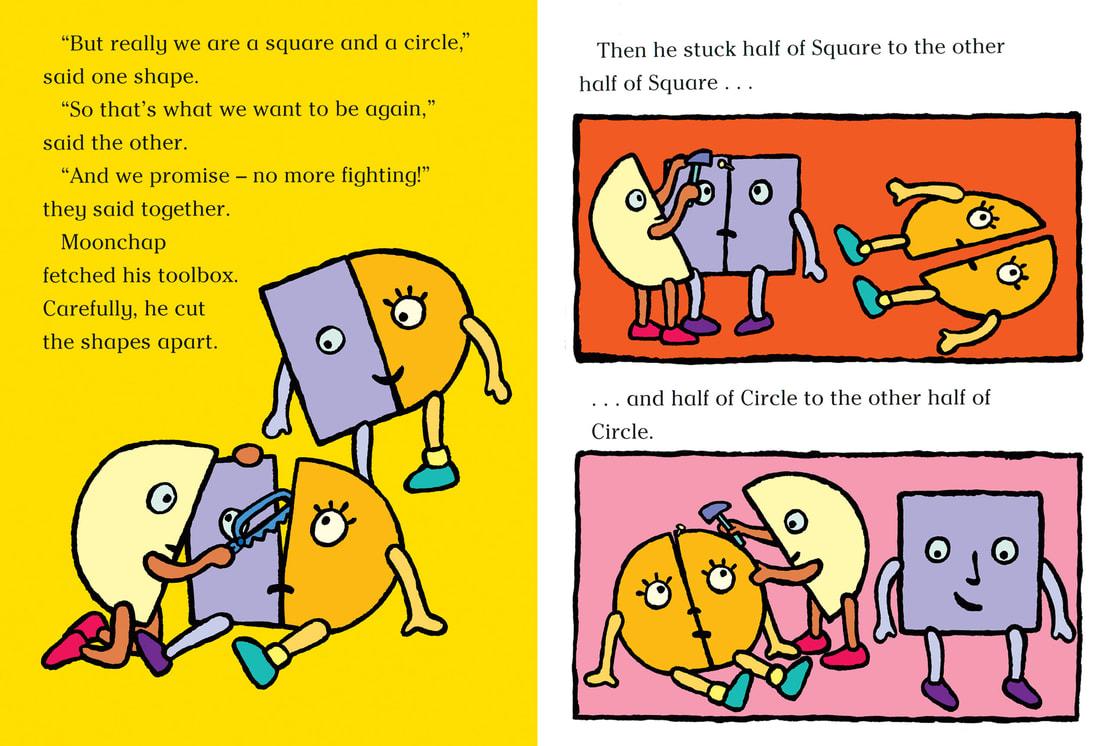

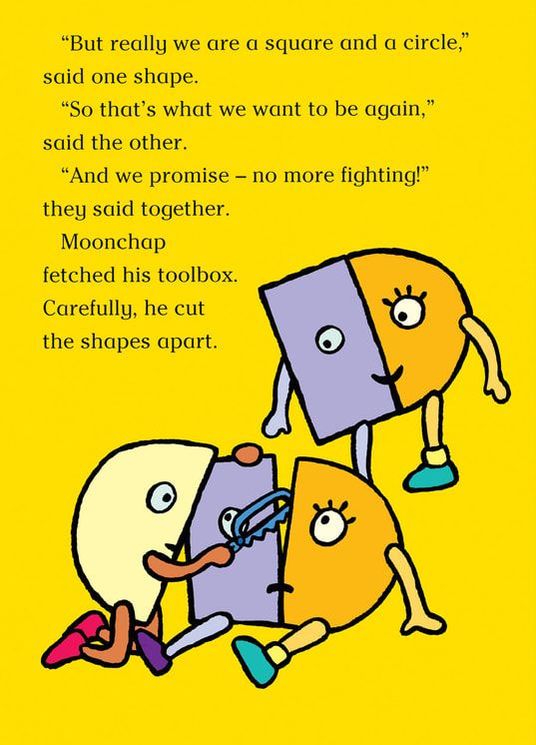

Illustrations copyright © 2003 by Mary Murphy from Moonchap by Mary Murphy. Flying Foxes. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations copyright © 2013 by Mary Murphy from Mouse is Small by Mary Murphy. Walker Books. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations copyright © 2003 by Mary Murphy from Moonchap by Mary Murphy. Flying Foxes. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations copyright © 2013 by Mary Murphy from Mouse is Small by Mary Murphy. Walker Books. All Rights Reserved.