|

Lisa Harkrader (Kansas) has authored two of our favourite mathematical stories, both of which were recently published by Kane Press, as part of its Math Matters series. 'A Fishy Mystery' (2017) and 'Ruby Makes It Even' (2015) cover the use of Venn diagrams and odd/even numbers respectively. To learn more about these stories, read our reviews, and find out where you can purchase them, simply click on their covers below. We hope you enjoy reading Lisa sharing her experience of working on these two mathematical book projects with you! Connect with Lisa: |

|

First thing first, three interesting/weird facts about you :-)

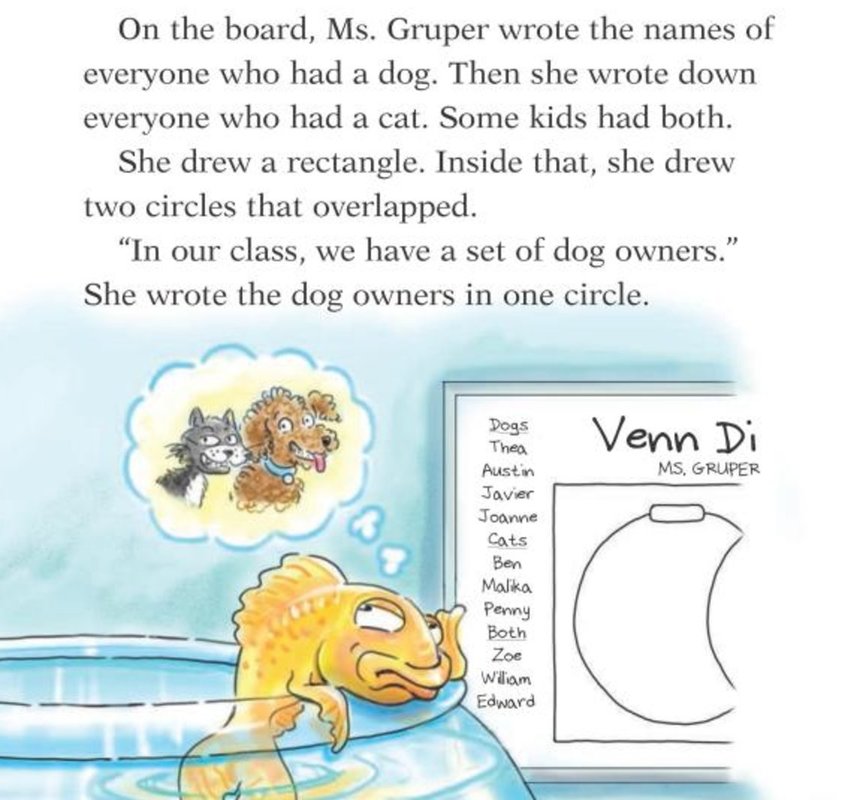

What inspired you to write picturebooks with a mathematical focus? Kane Press, my publisher, does amazing picture books with a math, science, or social studies focus. I loved their books, so I sent them some of my previous work and asked if I could write books for them. Happily, they agreed. How long did it take you to work on each of these books? From the initial one- to two-sentence idea to a detailed outline, then writing and revising the story, to the final edits after the illustrations and layout are in place takes about three months. 'A Fishy Mystery' and 'Ruby Makes It Even' focus specifically on Venn diagram and odd/even numbers respectively. What prompted you to focus on these topics? ‘A Fishy Mystery’ and ‘Ruby Makes It Even’ are both part of the Math Matters series published by Kane Press. For each book, the editors sent me some math topics the series hadn’t yet covered and asked me to develop ideas for the topic that most interested me. I liked the odd/even concept because odd and even numbers of things - or people - can each be useful in some situations and inconvenient in others. Also, I’ve always loved the way odd and even numbers complement each other, such as the way an odd plus an odd makes an even. I have a geeky love of Venn diagrams, so I jumped on the Venn diagram topic right away. I also love mysteries, and I realized that the three classic categories detectives use to solve crimes - means, motive, and opportunity - are really circles in a Venn diagram, and whoever ends up in the spot where the three circles overlap would be the culprit.

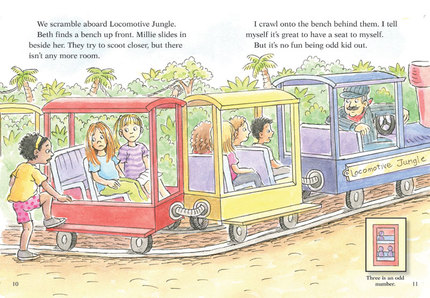

What were some of the key stages that you went through in creating these picturebooks? For both books, I knew the math concept first. My first step was to brainstorm until I came up with a fun way to use that concept in a real-life situation kids could relate to. Then I began developing the main characters, setting, and story problems that could be solved by using the math concept. Once the story was finished and revised, my editors sent it to the illustrator for sketches and final illustrations. Which of these stages did you find most difficult, and why? The most challenging part was coming up with the real-life problem that could be solved using the math concept. I wanted something interesting and fun readers could identify with. I’m a confirmed list maker, so my way of solving any writing problem is to make a list of possibilities. I set a timer for ten or fifteen minutes and tell myself I’ll list as many possible situations as I can, no matter how crazy, and not stop until the timer goes off. The first few things I write down are usually predictable and not very interesting, but the more I push myself, the more interesting the ideas become until I land on one that seems to sparkle on the page, and I know I’ve come up exactly what I need. For some maths picturebooks, the author is also the illustrator. In your case, you worked with illustrators. Did you find the experience tricky in having to communicate to other people what you had in your mind? My editors are really great about getting my input on illustrations. They send me the illustrator’s first sketches and ask for my input. They also send the layout when the text and final illustrations are in place and we make another round of edits so that the story and pictures work together as well as possible. "All the books in the Math Matters series feature kid characters grappling with problems in their lives and using a math concept to find a solution. I think this works well for the series in general and for my two books in particular because readers can see kids just like them using math in a real-world situation." When you worked with your illustrator(s), what key points did you ask them to bear in mind when creating illustrations for mathematical picture books? I’m very lucky that both illustrators were wonderfully creative. They took the story and added new dimensions to it in the illustrations. For example, the illustrations that show examples of the math concepts, such as the seating arrangements, were images my publisher made sure were included. Those visual elements - sidebars, diagrams, charts - are necessary for readers to understand the math concept of each story. My editors are the go-betweens that link the author and illustrator. Also, if something specific needs to be shown in the illustrations, I can send that information to my editors, and they make sure the illustrator understands it. The characters in both of your books are human characters. Do you find working with human characters easier than non-human characters (e.g. talking animals, animated objects, etc.)? All the books in the Math Matters series feature kid characters grappling with problems in their lives and using a math concept to find a solution. I think this works well for the series in general and for my two books in particular because readers can see kids just like them using math in a real-world situation. Closely related to the above point, some maths story authors prefer to have a context and setting as close to children’s real-world experience as much as possible. Others prefer fantasy. In the context of maths stories, what is your preference, and why? For the math stories, I like a real-world situation, because I want kids to see how math relates to real life. I want to show kids naturally turning to a math concept to solve problems in their daily lives. |

How do you know whether the language used in your stories is age-appropriate for your target children?

I spend a lot of time trying to craft sentences that use straightforward structure and simple words without making the language seem choppy or too simplistic. My publisher does ask that my math picture books be no longer than 1,000 to 1,200 words. I divide up the total number of words by the number of pages I have to work with (so I'm doing math at the very beginning!) and write each page with that number in mind. It usually works out to about 40 words per page or 80 words per spread. I want to keep the text from getting too dense on any one page and allow plenty of room for illustrations, diagrams, and other visual information.

On reflection of your maths picturebooks, how would you comment on the diversity of the books’ characters? Would you have done anything differently in terms of the diversity of the books’ characters? I think a lot about diversity when writing any of my books, but especially when writing books such as ‘A Fishy Mystery’, ‘Ruby Makes It Even’, and my books that have science or social studies tie-ins. I know teachers will use them in the classroom, and I want all students to be able to see themselves and more closely identify with the characters and story - and the math, social studies, or science concept. I’m lucky that my editors work closely with their writers and illustrators to develop books that embrace diversity. When I begin a story, I don’t know exactly how my characters will be portrayed in the illustrations, but I develop character names that lend themselves to diverse characters and I strive to create characters and situations that are universal, so that readers from diverse backgrounds and traditions can see parts of themselves in the story. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to read maths picturebooks? I think it’s important that kids see math as part of life, not a separate thing contained in a textbook used only to complete a worksheet. By seeing characters using math to overcome their everyday problems, readers can begin to feel comfortable with math and see it as a solution, rather than a problem. "I just want to encourage kids who are writing their own math picture books to really enjoy the process. I have loved writing stories since I was very young, and every day I am grateful that I get to continue writing the stories I love as an adult." What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own maths picturebooks? Any time you write about a topic, whether you’re a kid or an adult like me, you end up learning more about the topic and understanding it more thoroughly than you would simply by reading about it. You have to know the topic well enough to explain it in simple terms others will understand. When I write a math picture book, it forces me to look at the math concept from many different angles and think about how that concept works in real life. For example, I know abstractly what odd and even numbers are, but when I started developing the idea for ‘Ruby Makes It Even’, I had to think about how odd and even numbers affect us in everyday life. I just want to encourage kids who are writing their own math picture books to really enjoy the process. I have loved writing stories since I was very young, and every day I am grateful that I get to continue writing the stories I love as an adult. Do you think the use of storytelling in mathematics learning is only applicable to young children? Do you think this could be used in maths lessons in secondary schools too? I think math stories could be used to teach and learn math at any age. Upper level math many not seem relevant to older students until they see how it applies to something they love. For example, many older kids love baseball or other sports where statistics play a big role. Stories involving baseball may be the perfect way for them to learn concepts of statistics. For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own maths picturebooks at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the process, what would be your advice? I’m a big believer in brainstorming and pre-writing. I feel much more comfortable working out a story idea before I jump into writing the actual story. So I make lists, I create characters and snippets of dialogue, I outline the story to get the action and plot worked out. Once I’m confident that I know enough about the story, characters, and solution to get through to the end, I begin writing the actual manuscript. For teachers and parents who want to have a go at having their own maths picturebook published by a publisher, what would be your advice?

The best research is to go to the library or bookstore and read recently published books similar to the ones you are writing. Read them as a writer, paying attention to the characters, setting, structure, and tone. Make note of the publishers that publish books most like yours and then research them online. Almost all publishers have websites, and they usually have a section called CONTACT US or SUBMISSIONS that tells how they like authors to submit their work. What do you think of the research that we do and the resources that we provide to teachers and parents on our MathsThroughStories.org website? I love the MathsThroughStories.org website and the research you’re doing. I think a lot of kids feel anxious about math, and your research is showing new ways to approach teaching and learning math that makes it less scary and more integrated with a student’s life, putting the student in charge of the math, rather than letting the student feel like the math is in charge of him or her. I also love the research you’re doing with girls and math, since traditionally math has been thought of as more of a male domain. |

Illustrations copyright © 2017 by Cary Pillo from A Fishy Mystery by Lisa Harkrader. Kane Press.

Illustrations copyright © 2015 by MH Pilz from Ruby Makes It Even by Lisa Harkrader. Kane Press.

Illustrations copyright © 2015 by MH Pilz from Ruby Makes It Even by Lisa Harkrader. Kane Press.