|

Edward Einhorn (New York) has authored two of our favourite mathematical stories, both of which were published by Charlesbridge, and included in its 'Math Adventure' series. 'A Very Improbable Story' (2008) and more recently 'Fractions in Disguise' (2014) cover the topics of probability and fraction respectively. To learn more about these stories, read our reviews, and find out where you can purchase them, simply click on their covers below. We hope you enjoy reading Edward sharing his experience of working on these two mathematical book projects with you! |

|

First thing first, three interesting/weird facts about you :-)

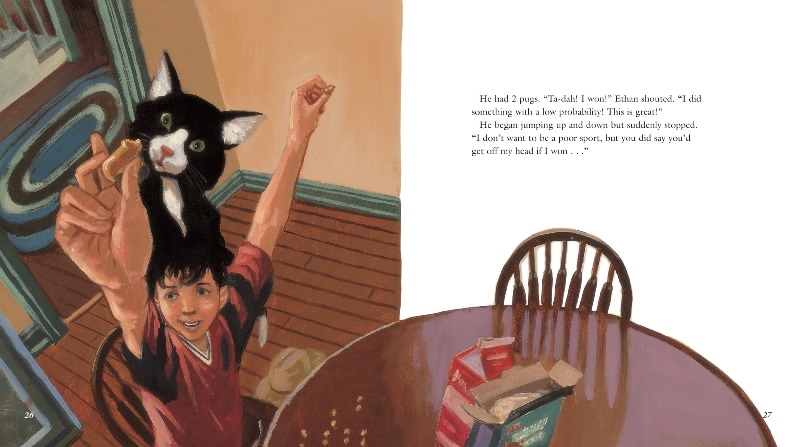

What inspired you to write picturebooks with a mathematical focus? I have always had a love of math and science as well as writing. When I first came to the city, I worked as a tutor, and teaching kids math was my favorite type of tutoring. It felt like this was a way to combine my interests. How long did it take you to work on each of these books? From the time I first wrote the book to the time it was published took about three years, both times. 'Fractions in Disguise' and 'A Very Improbable Story' focus specifically on fraction and probability respectively. What prompted you to focus on these topics? I was at a writing conference, and a school librarian told me she wished someone would write a picture book about probability. So I decided it would be fun to write one. Then, when visiting schools to promote my first book, I noticed that fractions came up a lot. So I wrote a book about that. What were some of the key stages that you went through in creating these picturebooks? First - decide which mathematical concept to focus on, then the characters and plot developed. There were many stops and starts with 'A Very Improbable Story', but 'Fractions in Disguise' came out almost the way it was published in the end. It just flowed. The illustrations came at the end, and the publisher found both illustrators. Which of these stages did you find most difficult, and why? For these two books, I wouldn't say that one aspect of the creative process was more difficult than another. But I have come up with some intriguing math topics and tried to write a story about them, only to find the story was a bit hard to come by. What I have done is put that first idea aside to work on another. I have learned that just because something is my first idea, it doesn't mean it is my best idea, and rather than try to force something that isn't working, being willing to try a lot of ideas quickly to see if they work can be a technique to find the perfect fit of idea and story. I also found the waiting most difficult. You have to wait for comments on the book, wait for the illustrations to be created, wait for it to be printed, wait for it to be released. But there are two great moments - when you first see the illustrations and when you hold the published book in your hand. For some maths picturebooks, the author is also the illustrator. In your case, you worked with illustrators. Did you find the experience tricky in having to communicate to other people what you had in your mind? The editor does most of the talking to the illustrator. I wrote a few illustration notes and clarified things when needed. After the pencil sketches came back, I made a few suggestions, and the editor told the illustrator. But both illustrators were very skilled, thank goodness, and I was pleased and excited by what they created. When you worked with your illustrator(s), what key points did you ask them to bear in mind when creating illustrations for mathematical picture books? I just wanted to check that the math was reflected correctly. The editor also looked out for that. The characters in both of your books are human characters. Do you find working with human characters easier than non-human characters (e.g. talking animals, animated objects, etc.)? There is one talking cat! I do tend to work with human characters more, but my main rule is I try to do whatever the story needs. In my Oz books, I have talking animals, and one of my favorite characters is a talking hat stand, called The Earl of Haberdashery. Closely related to the above point, some maths story authors prefer to have a context and setting as close to children’s real-world experience as much as possible. Others prefer fantasy. In the context of maths stories, what is your preference, and why? My preference is a world once removed from reality. Enough removed that there is a talking cat or fraction auctions, but close enough that kids still can relate. Our world, but cooler. On reflection of your maths picturebooks, how would you comment on the diversity of the books’ characters? Would you have done anything differently in terms of the diversity of the books’ characters? I’m a little sad that both of my published math books have a male protagonist, though it was partly the way that things worked out. There was a book with a female main character, but it never made it to print, unfortunately. It got close, but marketing decided against it (not because of the girl character, but because there was another similar book). I recently wrote another math-related book with a girl as the protagonist that I’m very excited about, and I’m hoping my agent gets it published. I do very much want to have a math picturebook with a female protagonist, I think it’s important to have equal representation. I decided after 'Fractions in Disguise' came out that any future math-related book would have a female main character, to balance out my first two books. I have also been thinking about the issue of other types of diversity in my picture books and trying to find ways to include that. The book that got stalled in marketing also had an Arab character (Al Gebra) and I envisioned the girl as black, though nothing in the text specified it. The new book is set back in ancient times and I envision a culturally diverse mix. These are important questions that I have been thinking about more and more. |

"I’m a little sad that both of my published math books have a male protagonist, though it was partly the way that things worked out. [...] I decided after 'Fractions in Disguise' came out that any future math-related book would have a female main character, to balance out my first two books. [...] These are important questions that I have been thinking about more and more." What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to read maths picturebooks?

I think that everyone learns differently, but one way that is very effective is through story telling. The same information presented in a dry textbook or in a more typical class setting can sometimes feel alienating. I want kids to be excited about math. I’m excited about math, and I hope that my joy about the subject comes through in my stories. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own maths picturebooks? I love the idea of having kids write their own books. I have learned so much through writing, because I love creating stories and that love extends to the subject I am writing about. It’s a way of discovering passion. Do you think the use of storytelling in mathematics learning is only applicable to young children? Do you think this could be used in maths lessons in secondary schools too? I think they can and should be used with kids in secondary schools and, for that matter, adults. As I mentioned in my earlier answer, I have a theater company that is geared towards adults, and we try to combine math and stories quite often! One never stops learning. For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own maths picturebooks at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the process, what would be your advice? Find the metaphor. Let’s say the subject is odd and even numbers. If numbers were people, what would they be like? How would odd people be different than even people (or would they)? What happens when they come together? Ask questions based on the initial math concept, then let your imagination run wild. After you’ve done that for a while, start shaping it into a story. The most fun part is often the imagining. Even if you don’t put it in the story, you learn from all the ideas that come up. For teachers and parents who want to have a go at having their own maths picturebook published by a publisher, what would be your advice? I got lucky. Someone suggested an idea, I wrote a book, and the first publisher I sent it to published it. But I did do a lot of research, looking at what publishers liked and reading submission guidelines before I sent out my story. Often, it’s good to try to get an agent first, they can help shape the book, and they know the different publishers and editors well. What do you think of the research that we do and the resources that we provide to teachers and parents on our MathsThroughStories.org website? I love MathThroughStories.org. It’s incredibly interesting for me to see these mathematical books and how they work for kids. Partly because I want to write better books myself, but also because I deeply believe that the split between math/science and the arts is an artificial one. I think we learn better and think better when we integrate knowledge from every discipline. A science writer I admire named EO Wilson wrote a book about it, called Consilience, which was one of the early inspirations for my work. |

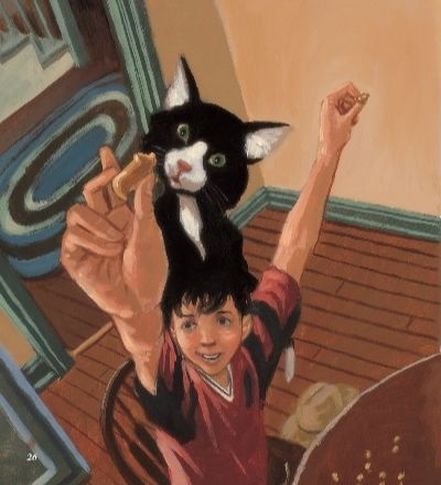

Illustrations copyright © 2008 by Adam Gustavson from A Very Improbable Story by Edward Einhorn. Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

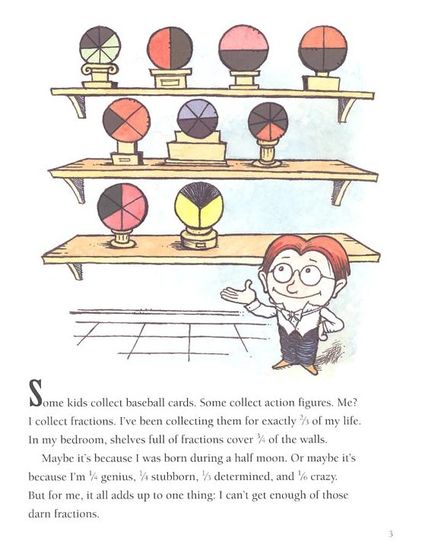

Illustrations copyright © 2014 by David Clark from Fractions in Disguise by Edward Einhorn. Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.