|

Donna Jo Napoli (Pennsylvania) has authored two of our favourite mathematical stories: 'The Wishing Club: A Story About Fractions' (2007) and 'Corkscrew Counts: A Story About Multiplication' (2008). Both are published by Henry Holt & Company, and illustrated by Anna Currey. (Donna co-authored 'Corkscrew Counts' with Richard Tchen) To learn more about these stories, and find out where you can purchase them, simply click on their covers below. We hope you enjoy reading Donna Jo sharing her experience of working on these two mathematical story projects with you! |

|

First thing first, can you tell us three interesting/weird facts about you :-)

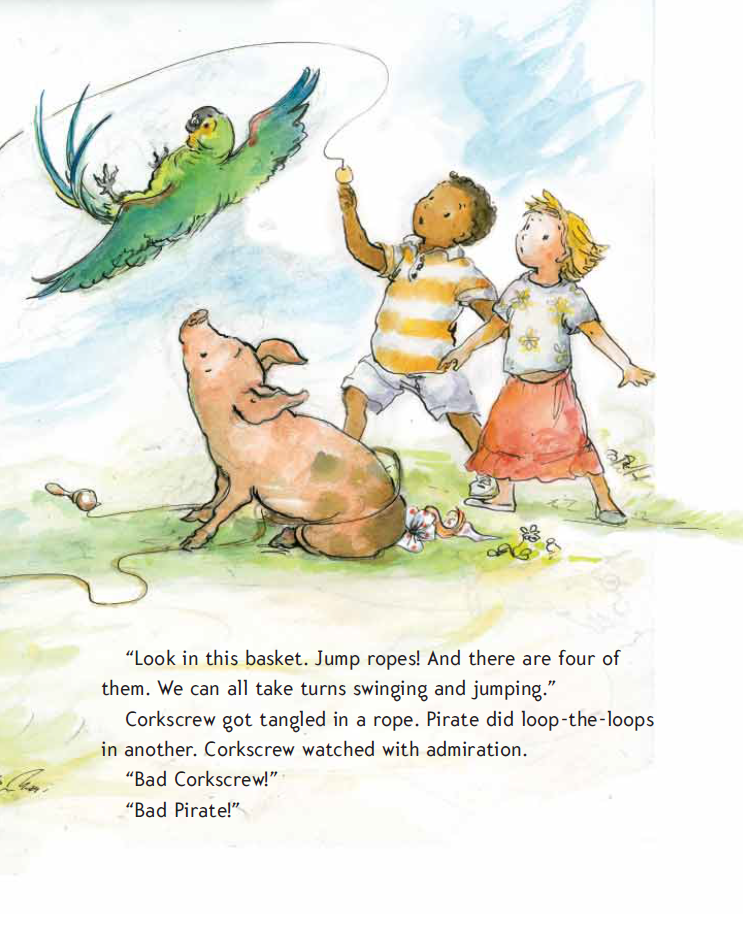

You received your BA in mathematics and Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures (both from Harvard University). That is a fascinating combination! Could you say a few words about where those academic interests came from? I loved school when I was a kid, and math was first, but languages were a close second. So I majored in mathematics. But my senior year of college, a language teacher suggested I go to graduate school in languages. So I tried it. And I quickly learned that I do not enjoy literary criticism. But the systems that languages use fascinate me – and studying that pulled in my mathematics foundation. So I became a linguist who looks at the formal systems of language. "[My son, Robert] was into math at a very young age [...]. If there weren’t enough sandwiches to go around, he’d cut all the sandwiches in two and give everyone half, then ask who was still hungry. [...] He made me happy. So I wanted to write math stories that would make children happy." What inspired you to write picturebooks with a mathematical focus? It came from my son, Robert. He was into math at a very young age (and eventually wound up majoring in it in college). But he always had such a sweet approach to problem solving. If there weren’t enough sandwiches to go around, he’d cut all the sandwiches in two and give everyone half, then ask who was still hungry. It was “math with a heart”. He made me happy. So I wanted to write math stories that would make children happy. 'The Wishing Club: A Story About Fractions' and 'Corkscrew Counts: A Story About Multiplication' focus on specific mathematical concepts. What prompted you to focus on these topics? Fractions and multiplication … wow, it’s hard to get through a day without dealing with one or the other or both. So everyone needs to feel comfortable with the concepts in these books. And the younger you can feel comfortable with them, the more confidence you might have as you approach other mathematical concepts. How long did it take you to work on each of these books? I wrote 'The Wishing Club' alone, and for some reason it just popped into my head. I must have written it in a few weeks, literally. But I wrote 'Corkscrew Counts' with a co-author, and collaboration always takes more time. We weren’t very slow, though. It might have taken us a couple of months. Did you find coming up with a storyline / context to embed your chosen mathematical concept in difficult? Where did you draw inspirations from? My husband grew up in South Dakota (until he was 12, when he moved to Iowa), and his first pet was a pig. He loves pigs. His study has pig pictures and pig sculptures all over the place. So the idea of children wanting a pig was a natural for me. And once we had Corkscrew, well, it was clear that he had to get involved in other adventures. What were some of the key stages that you went through in creating these picturebooks? I’m a storyteller first. So I started with characters and a problem – that is, children and the desire for a pig. Then I thought about how kids wish on stars. I got the idea that one might mistake a planet for a star. I’m not sure where that idea came from… it just did. (I’ve always thought people who could recognize the constellations were amazing. For me, that’s impossible.) That’s when the math kicked in. What might be the result of wishing on a planet? Well, it would be boring for the wish to simply be lost. But if the wish multiplied or divided the end result, that could be fun. But multiplication of pigs would mean tons of pigs – and I’m quite sure that parents would have refused to let tons of pigs into the house. So that would have meant a sad ending – getting piggies and then losing them. And fractions were no better – because who wants a piece of a pig? Ugh! But then I thought about fractions adding up to a whole. That’s when I came up with the idea of children of different ages, all getting a fraction of what they wish for, based on their age. Voilà – there was my story. Which of these stages did you find most challenging? Similarly, which did you find most satisfying? I loved how the children realized they had to cooperate in order to get a whole anything. That was very satisfying. The challenge? Hmm. I worried about how to make it feel natural that a family would just happen to have a two-year old, a four-year old, and twin eight-year olds. I didn’t want the math of it to feel like an imposition. But I couldn’t find a better alternative way to bring together children of those ages. So I just stuck with the family idea and hoped that people wouldn’t feel it was contrived. For some maths picturebooks, the author is also the illustrator. In your case, you worked with illustrators. Did you find the experience tricky in having to communicate to other people what you had in your mind? My editors are really great about getting my input on illustrations. They send me the illustrator’s first sketches and ask for my input. They also send the layout when the text and final illustrations are in place and we make another round of edits so that the story and pictures work together as well as possible. What were some of the key points that you and your illustrator had to take into consideration when creating mathematical illustrations? Illustrators and writers don’t generally work together. The publisher stands in the middle and deals with author and illustrator separately. I’m sure the illustrator had no trouble with making the pictures appropriate to the math until the end – when the pig idea came up. How do you show parts of a pig without being gross? I think the way the illustrator colored in various parts of the whole piggy was very smart (without being the least bit gross). The characters in both of your books are human characters. Do you find working with human characters easier than non-human characters (e.g. talking animals, animated objects, etc.)? No. I love working with animal characters, too. For the elementary crowd, I have some funny animal books. Among picture books I have 'Bobby The Bold' (about a bonobo) and 'Take Your Time' (about a tortoise). I wrote both with my daughter, Eva Furrow. Among novels, I have 'Mogo, The Third Warthog' (set in Kenya) and a trilogy about frogs: 'The Prince Of The Pond', 'Jimmy The Pickpocket Of The Palace', and 'Gracie The Pixie Of The Puddle'. Closely related to the above question, some maths story authors prefer to have a context and setting as close to children’s real-world experience as much as possible. Others prefer fantasy. In the context of maths stories, what is your preference, and why? I love fantasy; it takes you places you might never have imagined on your own. And I love realistic fiction; it allows you to consider the world you inhabit in a new way. Children need both kinds of stories. Which is better for math? I have to believe both can be wonderful. How do you know whether the language used in your stories is age-appropriate for your target children? I don’t worry about language complexity too much. More, I consider concepts and whether children might be cognitively ready for the concept. Children listen to adults talking all the time, and they become aware of the range of possible structures their language has via listening. When adults talk to school-age children, they don’t generally “talk down” in terms of language complexity – at least, I don’t. Don’t you think that would be annoying? Yes, sometimes I’m aware that a certain word might be new to children readers. In that case I ask myself if introducing the word to them is important. If I think it is, I use the word in a context that makes its sense obvious. That is, I wouldn’t want to make my reader go running to a dictionary. I want my story to stand by itself. So I work to use the right words in the right context. Word limits – well, for picture books, you generally don’t have more than around 800 to 1000 words. But that’s just a general guideline. If your story is aimed at 10 year olds, you might have 2000 words … it all depends. The type of limits you are talking about are generally for “easy to read” books. There a publisher might tell you that sentences should have no more than 8 words (or something like that) and that the whole book should have no more than 100 distinct words (or something like that). It all depends on the “level” of the book (they number them by difficulty with regard to reading skills). I’ve only done one “easy to read” book, so I don’t know all that much about it. |

On reflection of your maths picturebooks, how would you comment on the diversity of the books’ characters? Would you have done anything differently in terms of the diversity of the books’ characters? My characters had no physical characteristics other than age and gender when I gave the story to the publisher. The illustrator made white kids with rosy faces and very light hair. I was disappointed. So the illustrator added a darker tone to the skin and curled some of their hair. I think she did a good job compromising with me on that. I was grateful. She’s a very fine illustrator. Children need to see people like themselves in stories. And children in America are diverse – so the characters in the books need to be diverse – racially, ethnically, religiously, functionally, emotionally, and on and on. I am discouraged by how slowly the children’s publishing market has responded to the need for characters of diverse characteristics with diverse problems in a diverse world. But all writers need to buck up – not get discouraged – and keep writing stories appropriate to our children. The publishers are getting more and more receptive. Do you think the use of storytelling in mathematics learning is only applicable to young children? Do you think this could be used in maths lessons in secondary schools too?

I haven’t tried to do this, so I don’t know much about it. But I did write a novel for young adults that is essentially a medical mystery in that the main character has to solve a problem using the scientific method at a time in history when the scientific method wasn’t taught in school (the 1280s – in Germany). The book is called BREATH (because the main character has cystic fibrosis – for which they didn’t have a name in those days – but the mystery is not about his own illness, but about an illness that strikes his town). I have no idea if any of my readers learned about the scientific method from reading that novel. I would urge writers to try making a math novel. Why not? If it’s a good novel and on top of that it teaches math, well, hey, what could be better? "[P]icture books are just a cool way to introduce math because the narrative gives you a way of remembering the concept. Concepts that are presented out of the blue can work for some children, but not all. Most of us need a place to “hang” a concept – so we can regard it from all perspectives. A picture book gives that framework." What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to read maths picturebooks? Children can get the idea very young that math is “hard.” If math is in one of their picture books and if they have fun reading that picture book, well that changes everything. That means math is fun. So the picture books can give children a positive attitude toward math in general and toward their own ability to comprehend math, in particular. To me that’s essential. Beyond attitude, though, picture books are just a cool way to introduce math because the narrative gives you a way of remembering the concept. Concepts that are presented out of the blue can work for some children, but not all. Most of us need a place to “hang” a concept – so we can regard it from all perspectives. A picture book gives that framework. What do you think are some of the key benefits of helping children to develop their mathematical understanding by encouraging them to produce their own maths picturebooks? Anytime you give a child the tools for creating something on their own, you are empowering them. And the effects of that cannot be overestimated. I have a friend with cerebral palsy – she’s a quadriplegic. She is smart smart smart. But she couldn’t learn to read. It was really hard to get her eyes to track properly – and she just didn’t want to go through all that work. Then her teacher got the idea of having her tell a story and record it. The teacher printed the story and gave it to her. And my friend wanted to read her own story. She would have done anything to be able to read her own story. So she worked hard – and she learned to read. (And she eventually wrote her own story and published it – 'From Where I Sit' (Scholastic Press). Her name is Shelley Nixon. It’s a fine fine book.) Creating her own story empowered her. And it gave her the motivation to do the work necessary to gain an essential skill. When we put children in charge, they can do more than we ever might have hoped. For teachers and parents who want to encourage their children to create their own maths picturebooks at school or at home, but are not sure how to guide them through the process, what would be your advice? Encourage them to come up with real characters who have a real problem. Encourage them to think in terms of the types of stories they most enjoy. So if they love stories about people who do athletic feats, encourage them to think of someone trying to do something physical but who comes across a barrier and has to find the shortest way around it or through it or over it (what length ladder will they need, pitched at what angle?) – or something of that nature. Don’t have them start with the concept. That’s too abstract. Have them start with the story. That’s much more interesting. For teachers and parents who want to have a go at having their own maths picturebook published by a publisher, what would be your advice?

Not all publishers do math books. Look for those that do – and that specialize in them. Like Charlesbridge of Boston. Follow my advice in relation to the previous question. A story is a story first – and a lesson in something only second. Write a cover letter to the publisher and explain briefly (no more than a couple of sentences) that you teach math to fourth graders (or whatever) and you have written a book about children doing X (where X is some kind of action) for reason Y (where Y is something personal to them – NOT a concept). And say that the story is grounded in the mathematical concept Z. Ask if you can send the manuscript. OR get yourself an agent. That’s the better approach. There are just too many people knocking on publishers’ doors. They listen to agents more than they listen to the public. What do you think of the research that we do and the resources that we provide to teachers and parents on our MathsThroughStories.org website? MathsThroughStories.org is great. All the research is targeted at important areas. I particularly appreciate the work aimed at trying to figure out why girls generally are less likely to participate in advanced mathematics courses. Through review of literature, you show that the gap in achievement is not usually statistically significant when comparing grades 4 and 8, but much more boys do the A levels in math [a high school diploma in England] than girls do. Scientific studies can sometimes downplay societal factors. Your work not only doesn't downplay it, but you ground the study in what we have learned about feminist pedagogy. That's refreshing, and it has a chance of truly addressing the issue. What I appreciate about the resources the project provides is that you reach out to everyone. You help students, teachers, parents, anyone in creating their own math stories. You help scholars of pedagogy by providing them with relevant research articles. You help teachers by providing them with both "how to" and relevant research articles. You're holistic - and that's great, because sometimes a person thinks they are looking for one thing, but then they wander over to your other resources and find that they'd rather approach the issue on their mind in an entirely different way. You hold all the doors open. Kudos to you. |

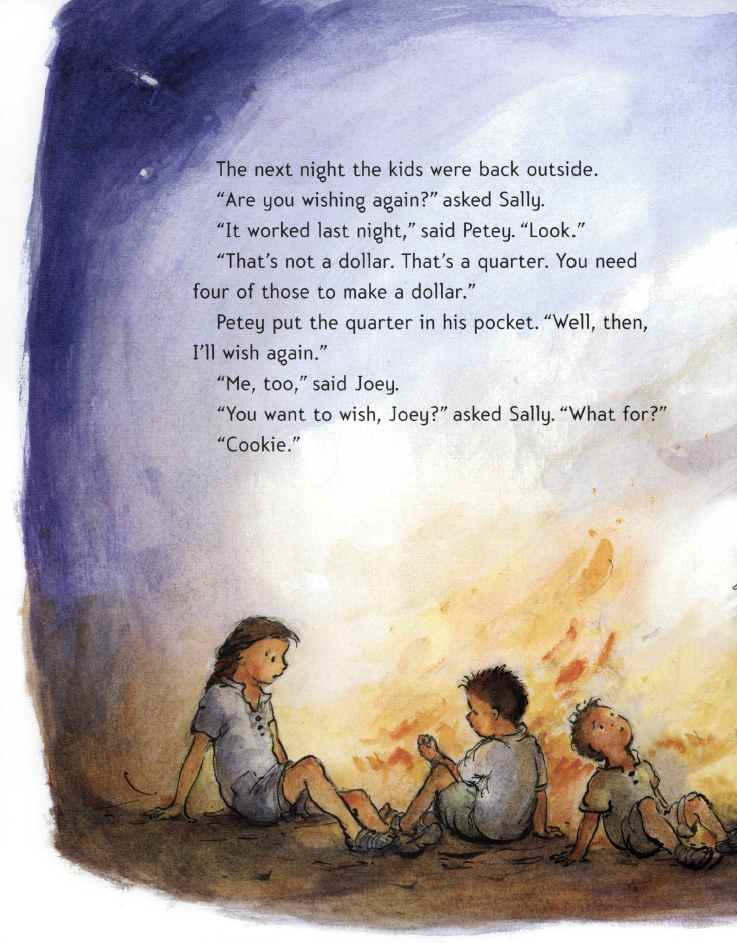

Illustrations copyright © 2007 by Anna Currey from The Wishing Club: A Story About Fractions by Donna Jo Napoli. Henry Holt Books for Young Readers. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations copyright © 2008 by Anna Currey from Corkscrew Counts: A Story About Multiplication by Donna Jo Napoli and Richard Tchen. Henry Holt Books for Young Readers. All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations copyright © 2008 by Anna Currey from Corkscrew Counts: A Story About Multiplication by Donna Jo Napoli and Richard Tchen. Henry Holt Books for Young Readers. All Rights Reserved.