Given the prevalence of picturebooks in children’s everyday school and home experiences, we decided to investigate how picturebooks about mathematics and mathematicians present identities for young readers to adopt or refuse. Many children begin to identify as “good at math,” or “bad at math,” or “not a math person” by a young age. We wondered how children’s literature might contribute to those self-classifications. What images and stories about mathematics are children exposed to? How might the stories shape and even limit how children understand what mathematics is?

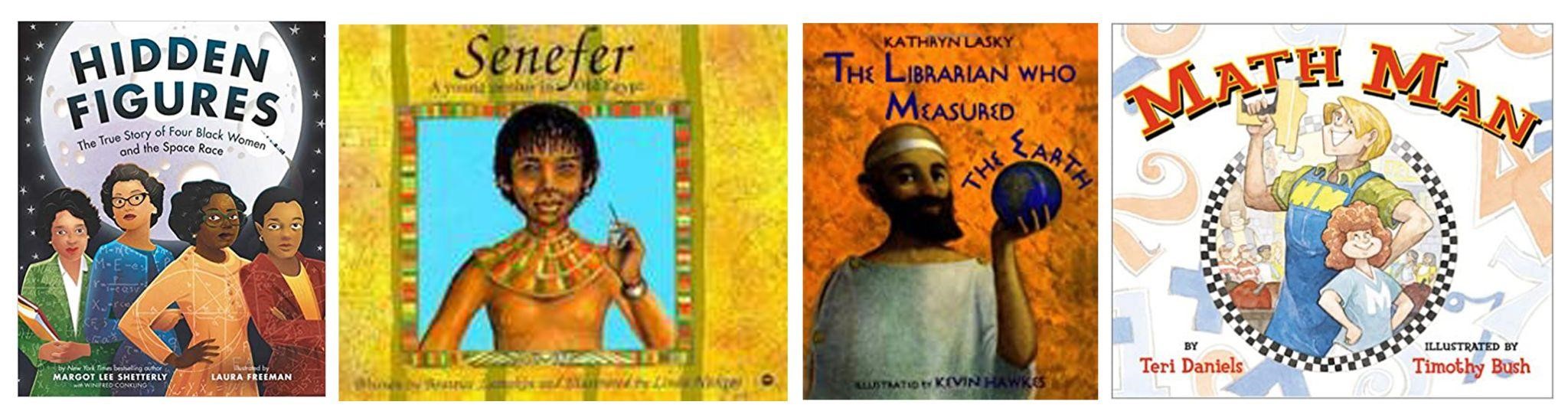

Many of the picturebooks we read are well-intentioned in rejecting the stereotype that mathematics is primarily a domain for boys and people of European descent. We applaud the number of books that reject the trope of white male dominance in STEM fields! However, it is still possible for children to absorb other subtextual messages that present limited and limiting views of mathematics. In this blog post, we share insights from our examination of 24 picturebooks and discuss four patterns (or hidden messages) we identified within and across the texts.

If you are interested in reading the full study, we encourage you to do so and let us know what you think!

Hidden Message 1: Mathematical ability is a gift

Books written to inspire readers belonging to identity groups that have been underrepresented in the narrative of mathematical ability may nevertheless mischaracterize what it means to be mathematically able. In ‘Hidden Figures: The True Story of Four Black Women and the Space Race,’ Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, and Christine Darden do not struggle with mathematical concepts or make mistakes. These women are paragons, though not ones that readers can realistically emulate, for their brilliance is preternatural, their mathematical ability pure magic.

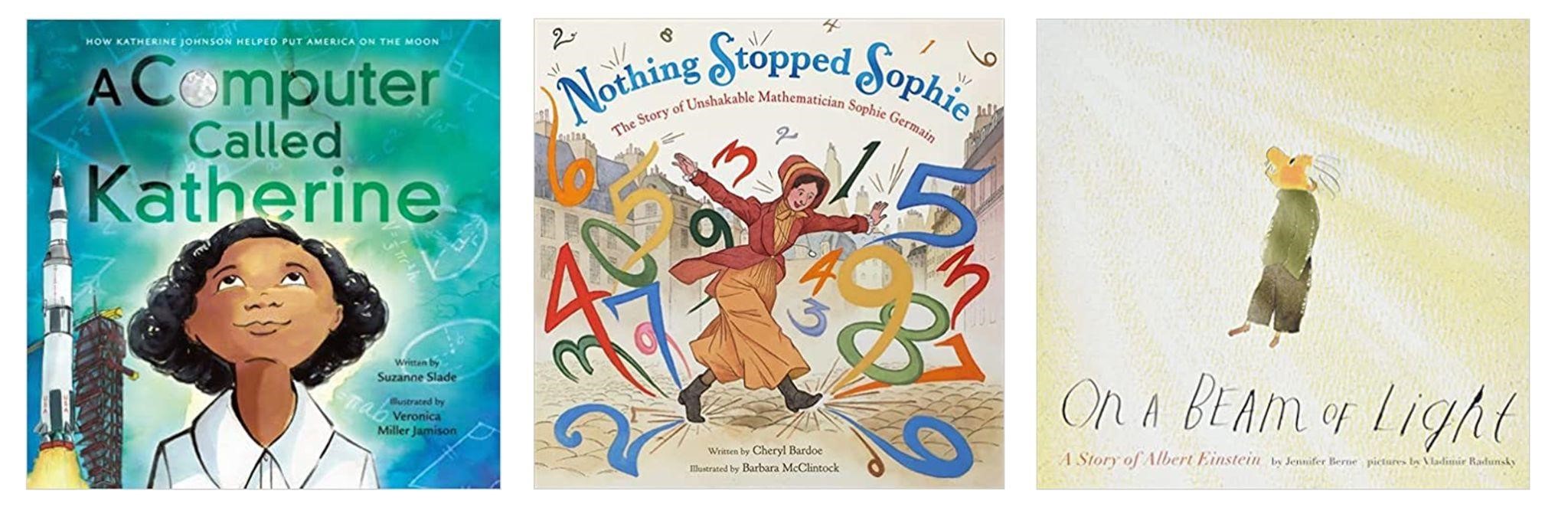

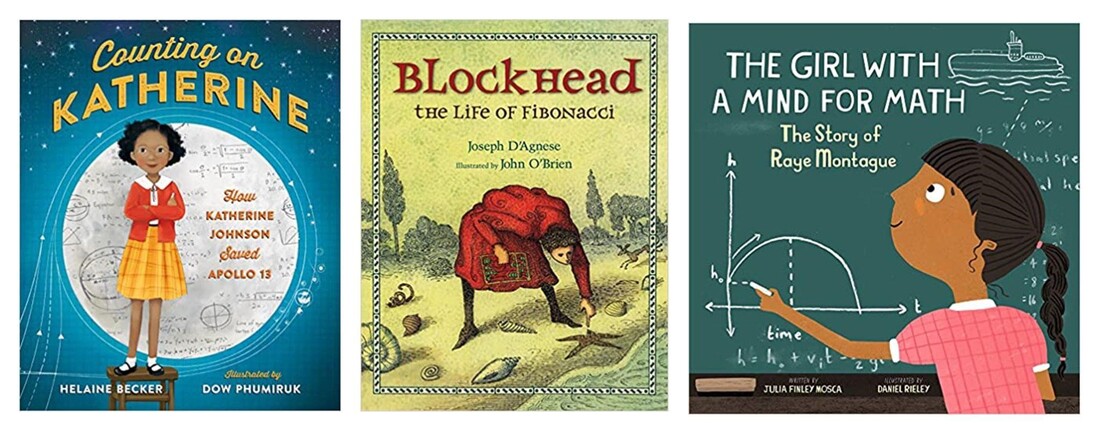

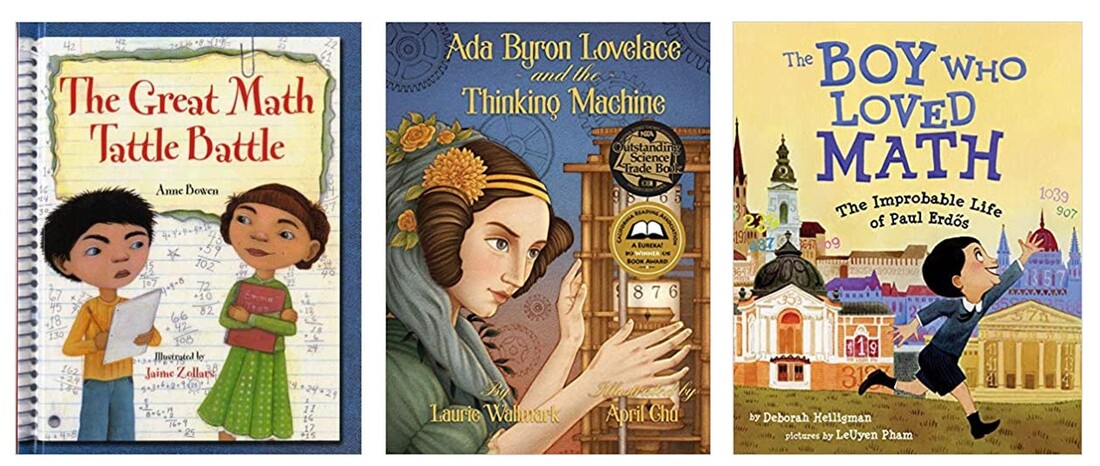

In ‘Hidden Figures,’ each of the four protagonists is referenced as being “good at math. Really good.” In fact, that phrase is repeated nine times throughout the book, leaving it to the reader to understand what it means to be ‘really good’ at math. Other picturebooks use similarly opaque wording. Paul Erdös “was the best. He loved being at the top in math” (Heiligman & LeUyen, 2013, p. 15). Albert Einstein was “a genius” (Berne & Radunsky, 2013, opening 14). Raye Montague was “a smarty” (Mosca & Reiley, 2018, opening 13). Senefer had “intelligence and abilities” (Lumpkin & Nickens, 1992, p. 10). Eratosthenes was “a real whiz in math” (Lasky & Hawkes, 1994, p. 13). Garth, a character in ‘Math Man,’ “had a way with numbers” (opening 5). Harley, the central character of ‘The Great Math Tattle Battle’, was “the best math student in second grade” (opening 1). Across these examples, readers encounter the archetype of the mathematical doer who owes their ability to some innate, ineffable gift.

The gist of this hidden message is that mathematical ability is an innate talent that one either possesses or doesn’t. Further implied is that those who possess ‘the gift’ are highly intelligent and may be geniuses. For them, mathematics requires little or no visible effort. Their work is intuitive and characterized by eureka moments. When innovation is reduced to eureka moments, and math is ‘a piece of cake,’ it obscures the perseverance associated with making sense of mathematical concepts. Children might misidentify themselves as mathematically incapable if it doesn’t come easily to them.

Hidden Message 2: Mathematical ability is like having a magic eye or knowing a secret language

In another picturebook about Katherine Johnson - ‘A Computer Called Katherine’ - the protagonist sees numbers up among the stars. Similarly, in ‘Nothing Stopped Sophie,’ a young Sophie Germain sees numbers vibrantly appearing out of thin air, superimposed over scenes of the French Revolution (opening 4). Although this might be a reasonable way to represent the thought processes of someone doing math in a picturebook, it might leave readers with the mistaken impression that talented mathematicians are people who literally see formulae floating around them.

For other picturebook personae, mathematics functions like a decoder ring for translating or decrypting the language of the universe. For Einstein, numbers “were a secret language for figuring things out” (Berne & Radunsky, 2013, opening 9). The idea that math is akin to language is not problematic on its own. The issue is with the exclusive nature of languages if one does not speak them and believes one cannot learn them. For a child struggling with math anxiety, it could be frustrating to see that mathematics is a language understood easily by its conversant speakers but is incomprehensible to outsiders. Although the language of math is openly taught in classrooms, it is a language many learners struggle to use fluently. We can easily imagine children feeling inspired by Katherine Johnson, but also saying “I never see numbers floating in the air, so I guess I’m not a math person.”

Hidden Message 3: Mathematics is about doing calculations quickly

Twelfth century mathematician Fibonacci tells us that when he was just a boy, his teacher “wrote out a math problem and gave us two minutes to solve it. I solved it in two seconds” (D’Agnese & O’Brien, 2010, opening 2). Early in ‘The Great Math Tattle Battle,’ readers are told that Harley Harrison “could figure out forty-five plus thirty-nine faster than you could spell ‘Mississippi’” (opening 1). Harley’s mathematical experiences render him as mathematically capable because he is fast and does not make mistakes. His spot at the top of the class is only jeopardized when he produces an incorrect answer and becomes vulnerable to Emma Jean encroaching on his turf.

For both Harley and Fibonacci, the focus is on the result rather than the process of making sense of a problem at hand. This hidden message reflects the tendency to overemphasize manipulation of numbers over relational thinking about mathematical ideas, which precludes (slower) processes of taking ownership of mathematical ideas through reasoning.

In ‘Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13’, readers encounter the message that mathematical ability translates to experiences of speed and correctness. When the Apollo 13 spacecraft was in peril, Katherine “did flight-path calculations, quickly and flawlessly, to get the astronauts home safely” (opening 13). ‘The Girl with a Mind for Math: The Story of Raye Montague’ contains similar messages about mathematical speed and heroism: “Would it take her a month? Maybe weeks for success? Well, it took CALCULATIONS (and tons of caffeine), but Raye finished in HOURS … just over EIGHTEEN! (opening 22). ‘YOU DID IT!’ they cheered, and her boss had to say that her quick mind for math had in fact saved the day” (opening 24).

Perhaps the goal of reading these and other picturebooks with children is to celebrate and normalize the contributions of Black women mathematicians. That is an admirable goal in and of itself! However, if the objective is to inspire children to view themselves as mathematically capable, it is counterproductive to insinuate that mathematical ability is based solely on innate speed and flawlessness. While speed and accuracy are important skills that need to be developed, having automatization take center stage is counterproductive to developing positive mathematical identities among young learners

Hidden Message 4: Mathematical ability is associated with social awkwardness

Few children yearn to be ostracized by their peers. However, one common message children receive about mathematics is that when you decide to devote time and energy to its pursuit, you may become a pariah, or at least socially awkward. This message is reinforced by numerous picturebooks. In ‘The Great Math Tattle Battle’, Harley Harrison and Emma Jean are the only two children shown to be interested in math. They are represented as being extremely annoying to their classmates. Eight centuries earlier, Fibonacci also annoyed his classmates, and later the townspeople of Pisa (D’Agnes & O’Brien, 2010).

In some picturebooks, characters find themselves with a choice to make: pursue mathematics or have friends. As a child, Albert Einstein “didn’t want to be like the other students. He wanted to discover the hidden mysteries of the world” (Berne & Radunsky, 2013, opening 6). Why is Einstein’s choice presented as mutually exclusive? Did studying mathematics preclude him from being like other kids? In the case of other picturebook personae, such as Ada Byron Lovelace, “numbers were her friends” (Wallmark & Chu, 2015, openings 7 and 16) and for Paul Erdös, “numbers were his best friends” (Heiligman & LeUyen, 2013, p. 11). Later, he made human friends when he met others who loved mathematics (p. 14).

We are concerned these picturebooks could leave young readers thinking, “I don’t want to be good at math because I don’t want to annoy people or be lonely.”

Conclusion

In our article, we offer an analysis of overt and hidden messages in picturebooks, and consider how these messages may contribute to the formation of young people’s identities as learners and doers of mathematics. Inviting children to examine messages about what it means to do math, and what constitutes being ‘good’ at math, are steps toward welcoming a greater swath of learner identities into the boundless world of mathematical inquiry.

About the authors

|

Dr. Olga Fellus is an Assistant Professor of Mathematics Education at Brock University (Canada). Her work focuses on the interface between teaching and learning mathematics, identity making, and educational change. Olga can be reached at [email protected]

|

|

Dr. David E. Low is an Associate Professor of Literacy Education at Fresno State University (USA). His research explores how children and youth critically theorize race, gender, power, and identity through multimodal texts such as comics and picturebooks. David can be reached at [email protected]

|

|

Dr. Lynette D. Guzmán is a former mathematics teacher educator whose scholarship focused on broadening the ways students explore mathematical ideas in classrooms. She is currently a content creator for her brand, WizardPhD, and creates videos that bring forward philosophical perspectives on various media (games, film, books). She can be reached at [email protected]

|

|

Dr. Alex Kasman received his PhD in mathematics from Boston University in 1995 and subsequently held postdoctoral positions in Athens, Montreal, and Berkeley. Since 1999, he has been a professor at the College of Charleston. He has published over 30 research papers in mathematics, physics, and biology journals. He also maintains a website that lists, reviews, and categorizes all works of “mathematical fiction”. The American Mathematical Society published his textbook on soliton theory in 2010 and the Mathematical Association of America published a book of his short stories in 2005. Alex can be contacted at [email protected]

|

|

Dr. Ralph T. Mason’s work focuses on mathematics education, curriculum theory, and pedagogy. He can be reached at [email protected]

|